Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In #religion

As I finished this review it became apparent that there are two main audiences for what I wrote - those that have yet to read the book and those that have already read the book. Therefore I decided to break the review up into two parts, one for each audience.

I've been listening to this podcast for years and even had a project several years ago with the lofty goal of responding to each and every episode. I did not achieve the goal, unfortunately. The problem was two-fold: 1. There are too many episodes 2. Nearly every episode is so packed with interesting content that my responses were taking longer than a week to prepare, so I was always behind.

The podcast is a model of how discussions can go, even when the topic is contentious. Justin Brierley is the epitome of civil. Like a good moderator, it isn't always clear where he stands on the issue - it's even easy to ignore the fact that he's a believer himself! He does an amazing job in the podcast of rephrasing what even his opponents state - skillfully steelmanning the entire time.

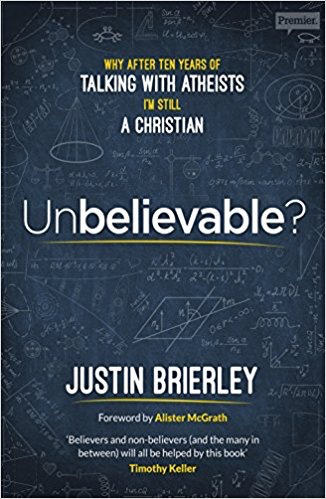

The book, Unbelievable? Why After Ten Years of Talking with Atheists I'm Still a Christian has all the best of the podcast in book form. It's a plea for a return to civil discourse on hard topics.

“Having conversations as one of the most important things we do in life“

“Many conversation descend into the equivalent of verbal hand grenades being lobbed over the barricades of our carefully erected worldviews.”

Brierley demonstrates how you can respect a position that you disagree with and how you can -- without fear -- present someone else's argument even better than they can. I can't help but think that this book was aptly timed for this age of quick sound-bites and tweets. We live in a culture where it seems to be acceptable to malign your opponent without addressing their concerns or characterize their positions in such uncharitable ways that everyone speaks past each other. It is a ray of light that this book - despite the fact that I disagree strongly with its conclusions - reaches across the aisle gently and respectfully with an invitation to engage in the discussion openly.

It is for this reason, out of respect, that I take a thoughtful, thorough approach to this review.

After the first chapter on "Creating Better Conversations," the book's chapters walk the reader through all of the standard arguments for God and Christianity, sprinkled with anecdotes from Brierley's interviews. The book reads very nicely and has a conversational tone, introducing the reader to some of Brierley's original reasons for believing - from personal experience and revelation - and many other reasons to support which belief that he admits came later along. The book is remarkably complete and as far as I can tell, hits all the major apologetics' points - including some arguments that have been circulating in the Christian community literally for thousands of years.

Brierley explains the Cosmological Arguments and the Fine Tuning Arguments in the chapter "God Makes Sense of Human Existence." The Moral Arguments, likewise, are addressed in the chapter "God Makes Sense of Human Value." He continues with arguments from purpose, the existence of Jesus, the evidence for the Resurrection, and suffering. Brierley finishes the book with a pragmatic explanation of living in the "Christian Story" and the benefits of choosing to live in that way. For anyone not familiar with the standard arguments for Christianity, Unbelievable? is a great introduction and summary of the primary arguments. For anyone who cares about civil and intelligent dialog, this book is for you.

If I am not convinced by these arguments and Brierley is where is the divide? I will hopefully address this question in the rest of this review. I break each of my responses into the appropriate topics, essentially following the order of the book, discussing where I disagree with Brierley's conclusions at many places.

I must admit that most of the chapters present so much of all sides of the arguments that the book is unusually balanced for its genre. It also means that this review is quite a bit longer than I would do for other books.

For Brierley, by his own admission, personal experience is the primary reason for his original conversion. He refers to a personal experience in a youth retreat in 1995, calling it a “moment of surrender“ where God "showed up," noting that most if not all Christians would probably relate to this.

"I suspect that something similar is true for most people who call themselves Christians. It's not that they can necessarily pinpoint a 'moment of surrender' like mine, but their faith is nevertheless grounded in an experience of God's presence in their lives, perhaps in some emotionally tangible way, or simply as a deep-down 'knowing' that has been there as long as they can remember."

I've never had such an experience, at least not tangibly, so I can't address Brierley's experience directly. However, we have learned from science that personal experience that isn't accessible to others doesn't typically track reality - it tracks subjectivity. People have profound experiences quite often and then interpret these experiences in all sorts of ways. This does not mean that those interpretations are correct, even if the experiences themselves are real. It is only through an honest exploration of the possible explanations, through prediction and skepticism, that we can achieve something close to the truth.

I don't think Brierley would disagree with this - which is why he goes to great pains to explore the evidence.

“My dad also said something else. As a scientist he found it intriguing that the emergence of life on our planet seems to disobey one of the fundamental laws of nature. The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that, when left to their own devices, all closed systems (such as our universe), will move towards increasing 'entropy' -- the scientific word for disorder.“

Every physicist will tell you why this is an incorrect statement - because the earth is not a closed system. Under the logic of this quote, even something like frozen ice would not be produced on the earth because it is a lower entropy state.

I've had a bad experience with this particular argument in University. The correction to the argument is both easy to find. Further, unlike other such arguments, you won't find any disagreement with any physicist you ask. It is the fact that the answer is so easy to find and consistent with the experts that there really is no excuse left to keep using this argument. Even so, I have seen Christians use it even after being corrected. The claim is so outlandish, from a physical point of view, that if a scientist actually believed it, they would have to admit that a frozen pond (also a decrease in entropy) would be impossible.

The claim presented in this quote represents a pervasive lack of imagination on the part of the theist where they seemingly can't wrap their brains around the idea that complexity can arise from natural processes. This lack of imagination infects not just this argument, but the fine tuning argument, other arguments from design, and even the moral argument.

Sean Carroll, an outspoken cosmologist from CalTech, says that the Fine Tuning Argument is the "theist's best argument" and it is well communicated in "Unbelievable?." The problem is that, despite the confident claims of many theists, the physicists are not at all clear how much fine tuning there is or if there is any at all. The way fine tuning is demonstrated starts with noticing that there are some seemingly arbitrary constants in our physical laws (e.g. speed of light, expansion rate of the universe, etc...). These constants if varied independently lead to conditions where life as we know it couldn't form. The emphasis here is to point out the problems with making confident claims about these observations.

With these objections, it seems premature to make any strong statements about fine tuning even if you are convinced it is there.

It is telling, I think, that the primary scientific arguments for God rely on the fringes of the known science into the unknown. William Lane Craig makes a great deal out of the absurd notion of something "popping into existence" from nothing - and to allow even one instance of it would allow things like bicycles to appear out of nothing. However, he doesn't address Sean Carroll directly who shows that models of the origin of the universe have some things able to appear out of nothing and other things not. These models actually make predictions for things we may observe, e.g. correlations in the microwave background, values of the early universe entropy, etc... What predictions do the theistic models actually make about the properties of the observable universe? None to my knowledge. It is clear that science and religion are playing by different rules here.

Brierley comments about the argument from contingency,

"I've been struck by the obvious yet remarkable fact that there is anything at all. [...] Like Leibniz, I can see that it's perfectly logically possible that there could have been nothing at all.

I am not a philosopher and am unconvinced by words like contingent and necessary. For example, I do not see any support for the claim that there are necessary objects, or that a being or mind could satify the requirements to be necessary. Maybe the only things that can be necessary are things like laws of logic, and that objects don't fit that criterion. I don't know! But until these are actually demonstrated and not just asserted, all of the arguments based on them have no content. In the same way, perhaps the concept of "nothing" isn't well defined and can't manifest in reality, so the question "why is there something rather than nothing" is answered simply with "because 'nothing' isn't realizable".

Further,

“There’s nothing about our universe to suggest that it had to exist rather its existence is contingent. It needs an explanation of his existence.”

I would add as an analogy that there’s nothing about our experience on the Earth to suggest that the Earth is round or that it orbits the sun. It may be logically possible to have a flat planet, but not physically realizable in our universe (note: the spherical nature of planets is due to the spherical form of the law of gravitation). Our intuitions do not always track the truth, and truth should be our goal. As a scientist, I am accustomed to cases of seemingly obvious things being false, and of seemingly impossible things being true irrespective of our intuitions. Thus, strictly philosophical arguments are not enough to demonstrate the existence of something.

Why is the universe written in the language of mathematics? Brierley says,

For those who want to ask `Why?', atheism's only answer seems to be that it is a massive coincidence.

I don’t see it as a coincidence I see it as a requirement. In any universe that has any patterns at all such that life could possibly exist - no matter what form of life - then those living beings would discover those patterns as the "mathematics" of that universe. It doesn't surprise me that there are patterns in the universe, but I still agree with Brierley that it is an amazing thing that the universe exists at all.

"So does science provide iron-clad proof for God's existence? No. Could the scientific consensus change in the future? Of course it could. Is this all there is to say on the subject? Certainly not. The case for God is a cumulative one that reaches well beyond science..."

Although I can quibble about the use of "proof" here (science doesn't deal in proof, only evidence) I'd rather take the time to extend the notion of "science" to include things like history as well as the study of morality, which moves into the next chapters. Really, what I am thinking is that rational discourse combined with skeptical attitudes are the components that include science and these other topics. In the case of the universe existing, perhaps an "I don't know" is the best answer we have right now, until someone is imaginative enough to find a way to determine it. To posit the answer "I know, and it is God" requires a level of explanation and prediction far above what any theist seems able to give.

In discussing human value, Brierley writes:

"It was grim stuff, admittedly, but it was a moment which exposed the problem for atheists who affirm the subjective nature of morality but then find themselves in a bind when it comes to truly horrendous acts. They don't just feel wrong. They are wrong. Period.

He concludes the chapter with,

"I have tried to persuade you of two things in this chapter. First, that humans have a real inherent worth and dignity that transcends a purely evolutionary story of how morality came to be. Second, if humans have such a value then it only makes sense if there is someone beyond nature who can assign them such value, the God who created them in his own image.

I am not generally swayed by the moral argument for a few reasons. First, I think that much is made out the subjective/objective dichotomy that someone like Sam Harris already handles consistently. In The Moral Landscape, he is able to define morality as the concern for the suffering and well-being of conscious creatures which, even if done imperfectly, coincides well with all of the sorts of problems we associate with moral choices. In this way, he describes an objective basis for morality without resorting to outside agency.

My second issue is that the supposed solution - "God did it" - fails the "Euthyphro dilemma" - the question whether something is good because God wills it or whether God wills it because it is good. In the former, we get the repugnant conclusion that if God commands murder it is necessarily good (the good of a dictator). In the latter, the good transcends God so we don't need God for the existence of the good. The only way out of this dilemma that I have ever heard is the claim that "the standard of the Good is God’s very nature" (William Lane Craig) or something similar. This seems to me to be word games to define your way out of the problem.

My final issue with the moral argument is that it seems to me that, like the argument from personal revelation, the argument itself relies on the intuitive notion that there are some things that are objectively wrong: things like murder and rape are objectively wrong, to deny this seems abhorrent, and everyone has this intuition. Since, in other contexts (e.g. flat unmoving Earth), we have already seen that our intuitions fail in many situations, is it possible that it is failing here and we just don't see it?

To explore this line of thinking, one should notice that in the moral argument the usual extremes are always trotted out - murder and rape - and not something a bit more ambiguous. Since this argument holds a lot of emotional weight, perhaps we can explore this in a different way, and leave ourselves at least agnostic on this issue. We have here some models of the source of morality - and I am neither promoting or denying any of these:

There may be others, but let's stick to these for a second.

To me, all three models explain the perception that murder and rape are objectively wrong. It would seem obvious from an evolutionary perspective that for social creatures, murder and rape would feel objectively wrong. These three models all predict that we would have some divergence on more subtle issues, although I think not to the same degree. Model 1 would further imply that even on these more subtle aspects of morality there should eventually be convergence - the moral status of same-sex couples, for example. Models 2 and 3 would imply that there would be huge cultural differences between groups on the more subtle questions. Given our observations, this would seem to be evidence against Model 1 and the moral argument for God.

In either case, if you have Models 1-3, a scientist would require further predictions that would help us actually distinguish between an agent-imparted standard and one without, even when both are consistent with our intuition about the extreme moral questions. To say more would be presuming what the data would be without actually testing it. We land, then, at least on the side of unconvinced but perhaps hopeful for the moral argument.

"You and your beliefs are the product of a long chain of inevitable physical events. [...] It's all just a series of physical events - billiard balls bouncing off one another. They aren't the least bit interested in the truth or falsity of the thoughts they are producing.

Understanding the self-defeating nature of the naturalist worldview was a penny-dropping moment for me. It meant that seeking meaning of any sort was a self-defeating enterprise for a thoroughgoing atheist. Just as the collisions of the balls on the billiard-table only mean anything if there is a player who intended them to find a pocket, so we must be more than the matter that makes up our brain.

Here again, I think Brierley is failing from a lack of imagination. Meaning is a structure we attribute to actions and events in our lives. It seems to follow naturally from our pattern-seeking tendencies combined with our goals to increase well-being. I find nothing too problematic with this view, even if we don't currently understand the detailed nature of consciousness.

There is a downside to notice for the "meaning from God" perspective, and that is the fact that the notion of eternal life in heaven makes this life not have any meaning, due to its finiteness. Even if this life is supposedly a test for admission, the fact that the current life is finite compared to the infinite afterlife is enough to rob it of any significant meaning. Clearly there are arguments on each side for this, but I just wanted to point out that it isn't completely clear even on the theistic perspective.

Brierley nicely summarizes the historical arguments, both in the establishment of the existence of Jesus and the arguments of the Resurrection. My largest concern with these arguments is the amount of trust that is placed in historical methods. When confronted with the idea that we can't know the details of historical events to the level of repeatable, physical experiments, most people don't seem to take issue. However, the claim that someone rose from the dead is something that - in a modern context - we'd want medical records, corroborating physical evidence, and we'd still be pretty skeptical that someone was putting us on. Placing these events two thousand years ago, written decades after the events, by largely anonymous sources should make us less confident in the claim, not more.

The minimal facts approach to the historicity of the Resurrection seems to be a major selling point for Christian apologists. Although not a historian myself, I have read enough to see that this approach seems to never be used for any other historical event - why the special case? I have personally found that the response by Matthew Ferguson - who is a historian - is as complete a response that one will ever find, and haven't seen anything even remotely convincing as a reply.

I'll start my response here to point out that the argument from suffering is not the atheist's greatest objection. Like Matt Dillahunty, in my opinion the greatest objection to the theistic claim of the existence of God is from hiddenness. True to Brierley's form, he grapples well with all sides of the issue of suffering, bringing in all of the typical theistic counter arguments - but they are all indirect. He implores us to appreciate how the preponderance of the other arguments for God "tips the scale towards belief in God." He puts forward the idea that the objection is baseless because of the lack of objective morality under the atheist worldview.

"it's difficult to see how the reality of a world of moral right and wrong can exist in the absence of God. But the question being asked by the atheist is a fundamentally moral one."

He appeals to mystery,

"it is a mystery we believe will be answered in a day of final justice and joy when Jesus Christ sets the world to right."

and free will, hidden purpose of suffering, and an allegory. Books have been written on this problem, and this chapter summarizes the topic nicely. I am not moved by it because it feels to me - like all treatments of this topic - one excuse after another with nothing to pin it down. As Sam Harris says, one can always answer the question "is suffering and evil consistent with God?" with a "yes" - the better question to ask is, "does the suffering we observe in the world suggest there is an all-knowing, benevolent God?" To that, the answer is clearly "no". Sure! You can always come up with reasons for the former, but the later is much clearer.

The really big objection, in my view, is hiddenness - the lack of obvious indicators of a divine presence. If God actually wants a relationship with people then God's lack of obvious existence is completely inconsistent with that, in a way that appealing to free will, the purpose of relationship, allegory and mystery just don't work. If you look at nearly every one of my responses, it really comes down to not being convinced due to the lack of unambiguous evidence.

I could go on with this review, but it is long enough as it is. I applaud Brierley's efforts in summarizing 10 years of conversations on this topic. I totally endorse his goal of improving conversation on difficult topics; and his tone in this book and the podcast should be a model for everyone. Perhaps Brierley's book is just one more data point of confirmation bias, and perhaps my review is also. How do we get past that? The best way is to have the conversations, honestly and completely, and to constantly question your own perspective. I want to thank Brierley for his fine work and hope he continues these efforts far into the future.