Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In #religion

In the Unbelievable podcast episode Do extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence? Jonathan McLatchie vs Jonathan Pearce I was struck by several claims and points, especially made by Jonathan McLatchie. I went back and listened to two other debates with him, one with Matt Dillahunty and one with myself and found some of the points Pearce made against McLatchie were things that both I and Matt had brought up -- mostly about McLatchie's apparent over-fondness for stories over real evidence.

Jonathan McLatchie talks about cumulative cases, using the vocabulary of probability theory, such as,

If you have two pieces of evidence each with a base factor of 10 and then combined they have a cumulative base factor of 100.

He thinks in terms of independent data pushing the likelihoods up and down so that once you've used one data point to update the likelihoods, you can start with that updated likelihood with the next data point -- ignoring any possible dependency between one data point and another. As we see below, it also ignores priors. This makes the process easy, but it leads to false positives which can be seen in a trivial example.

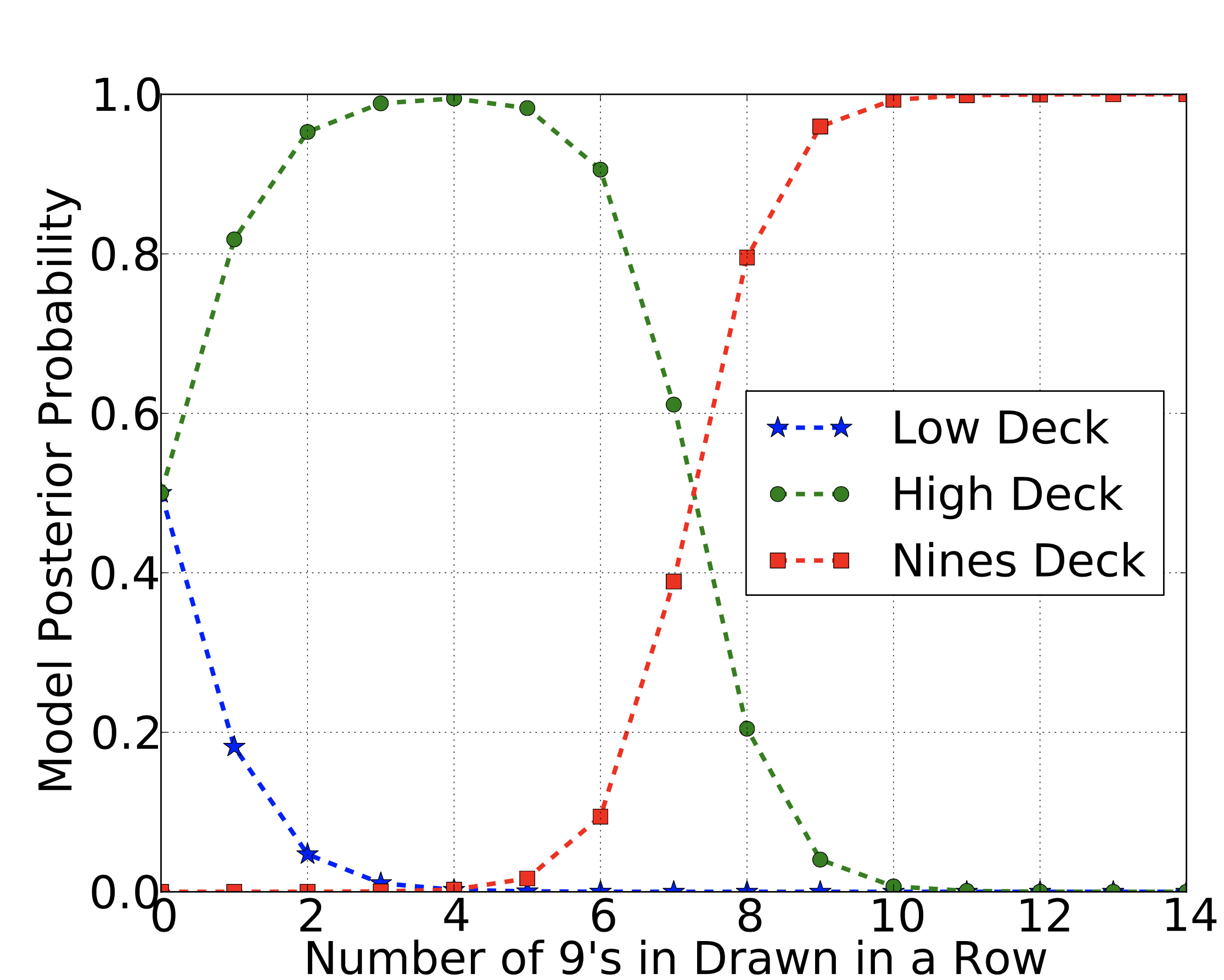

For example, in my book Statistical Inference for Everyone, I use an example of drawing cards from a deck of (unusual) cards and trying to infer which deck. At some point we have drawn a number of 9's (with replacement) in a row, and are trying to infer whether the deck is a so-called High deck (which has 10 10's, 9 9's, 8 8's, ... , 2 2's and 1 A ), a so-called Low deck (which has 1 10, 2 9's, ... , and 10 A's), and a so-called Nines deck (which has all 9's). The Nines deck is a-priori a lot less probable, because we were simply told that there were two decks -- High and Low. However, after many draws of 9 in a row that claim seems less likely.

Using Bayes factors alone, the data would only support the Nines deck and miss the actual (correct) inference.

Another problem with ignoring priors is that it commits you to believe many other crazy claims and would lead you to believe in psychic octopuses. I made this point with McLatchie and so did Matt Dillahunty -- if you have a flawed epistemology then you will be forced to either believe in crazy things or be inconsistent and hypocritical.

McLatchie states,

The hypothesis that God has used miracles as authenticating signs predicts that they will stand out against the normal course of nature. The fact that miracles do in fact stand out against nature cannot be taken as evidence against miracles because the hypothesis predicts very strongly that's what you'll find.

What McLatchie doesn't seem to see is that regardless of the source any purported cause of an event which is rare has a low prior, which should be used against it when comparing to other causes with higher priors. Since God is supposedly using miracles as "authenticating signs", if you are going to interpret any particular event as a miracle you have to overcome the low prior -- "authenticating signs" would be rare -- support it with stronger evidence than would be needed for a more mundane explanation.

I would further ask McLatchie, why should authenticating signs be rare in the first place? Why couldn't God make a miracle like his name written in the clouds every time the sun comes up, to authenticate his existence and power? Also, would McLatchie have to be making arguments like this if God were a lot more obvious?

The one that really perplexes me is Jonathan's perspective on the prophecy that Jesus would be executed on Passover (or around Passover, depending on which Gospel you read).

another example would be that jesus death coincides with the feast of passover so jesus dies [on Passover or around Passover] according to all four gospels [...] so jesus in the new testament is presented and portrayed as the fulfillment of that passover lamb that he is the ultimate passover lamb that the passover feasts pointed to and so it's quite a coincidence it's quite fitting then that jesus death coincides with the feast of passover that's the strength [...]

There are very good story-reasons for having this be the case, the authors of the Gospels knew the Old Testament stories, and could interpret the Jesus story in light of them and write the story accordingly. This is so straightforward an explanation, with very little to counter it -- even if you believe the writers to be eye-witnesses. All you'd need is for Jesus to be executed sometime in the vicinity of Passover, a short time of an oral tradition or retelling of the stories by the same people (which get naturally embellished) and you've got it. McLatchie's argument is so uncompelling for anyone who isn't already convinced that it is remarkable.

Another argument made by McLatchie is the supposed use of "undesigned coincidences" in the text.

From one of his responses to Richard Carrier, McLatchie writes,

the most classic form (which Carrier is attempting to define) is when you have multiple (at least two) accounts that report an event where one account answers in passing a natural question raised incidentally by the other. Contrary to what Carrier asserts, the argument has never been that such features prove there was a real story. Rather, such features are evidence that a real event lies behind the reports found in the gospels — that is to say, the presence of an undesigned coincidence is more probable given the hypothesis of historicism than given the annulment of that hypothesis. Some undesigned coincidences contribute greater evidence than others. Carrier’s lack of nuance in his description of the basic argument does not get his article off to the best start.

I think my biggest problem with this line of thinking is that there are major differences between the narratives in the Gospels. For example, the nativity narratives are contradictory -- just try to map out the path Jesus' parents take. The resurrection narratives too do not agree with each other, like the number of people coming and going, whether things were open or closed, or who actually saw Jesus. When apologists have to make arguments (i.e. the text is not clear) to justify seeming discrepancies in large events, why should we pay attention to subtle agreements? Why should we be surprised that there are some agreements, when we know that there are literary and other source dependencies between the anonymous writings of the Gospels? Again, McLatchie's argument is so uncompelling for anyone who isn't already convinced that it is remarkable.

It is striking how many recent apologists use Bayesian reasoning yet ignore the prior -- which means they really aren't using Bayesian reasoning but want to just sound like they are. This is a form of dishonesty, I feel, but at best it is a clumsy analysis -- and a problem that has been pointed out for the McGrews, Calum Miller here and here, Blake Giunta, and of course mentioned in my conversation with Jonathan McLatchie. The use of Bayes Factors, which also ignores priors, is indicative of this approach. Why do apologists want to ignore priors? Because what they are arguing for is, a-priori, seriously unlikely.