Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In #religion

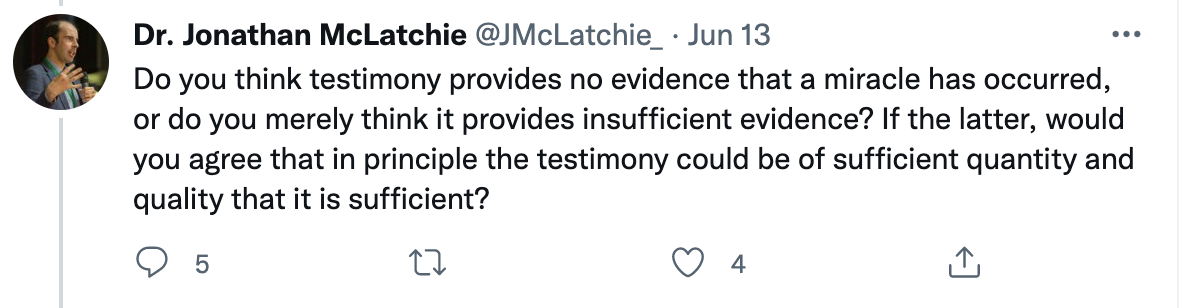

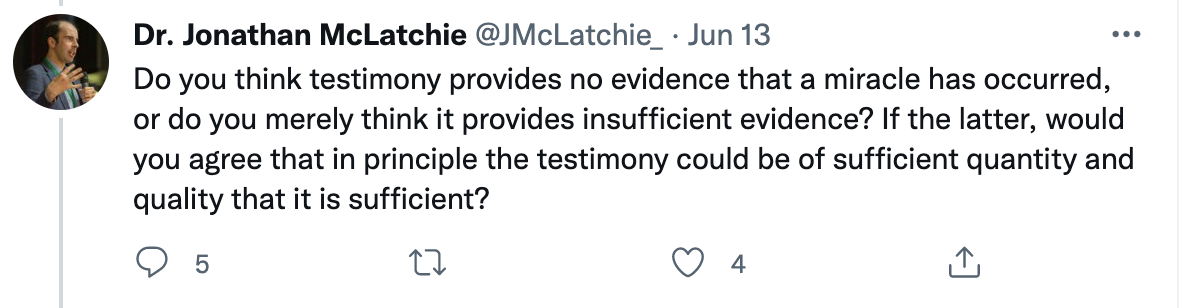

When asked the question raised by McLatchie,

I would have to say that new testimony does not raise my probability for a miracle, mostly because all prior attempts to do so have been debunked or at best shown to be profoundly unreliable. This lowers my credence in the sources, even if I don't have time to investigate in detail the next new claim. Am I being hyper-skeptical? I don't think so -- I'm simply adjusting my beliefs to the evidence, and that evidence is that miracle claims have not met their burden of proof. How could this problem be addressed for me? In modern settings, having randomized-controlled studies of miracles would be the best -- because those claims that use this process have shown themselves to be reliable, and thus <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>→</mo><mn>0</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a\rightarrow 0</annotation></semantics></math> in the model described below. Given modern miracle claims, and their issues, I don't think that any ancient source could convince me of miracles -- their reliability on matters of the physical, chemical, and biological world has been shown to be terrible, thus <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>→</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a\rightarrow 1</annotation></semantics></math> in the model below.

Although this model is a simplification, it is useful to see that the adjustment of probabilities needs to be taken with care and that unintuitive and non-monotonic effects can easily occur (you can see another non-monotonic effect with the high-low-nines deck example shown here). Even if for a single data point, the probability of a model increases, the same can't be said of an accumulation of data points unless one is sure that all of the simplifying assumptions are correct -- and they never are.

In response to Paulogia's tweet:

Jonathan McLatchie has a reply that got me thinking:

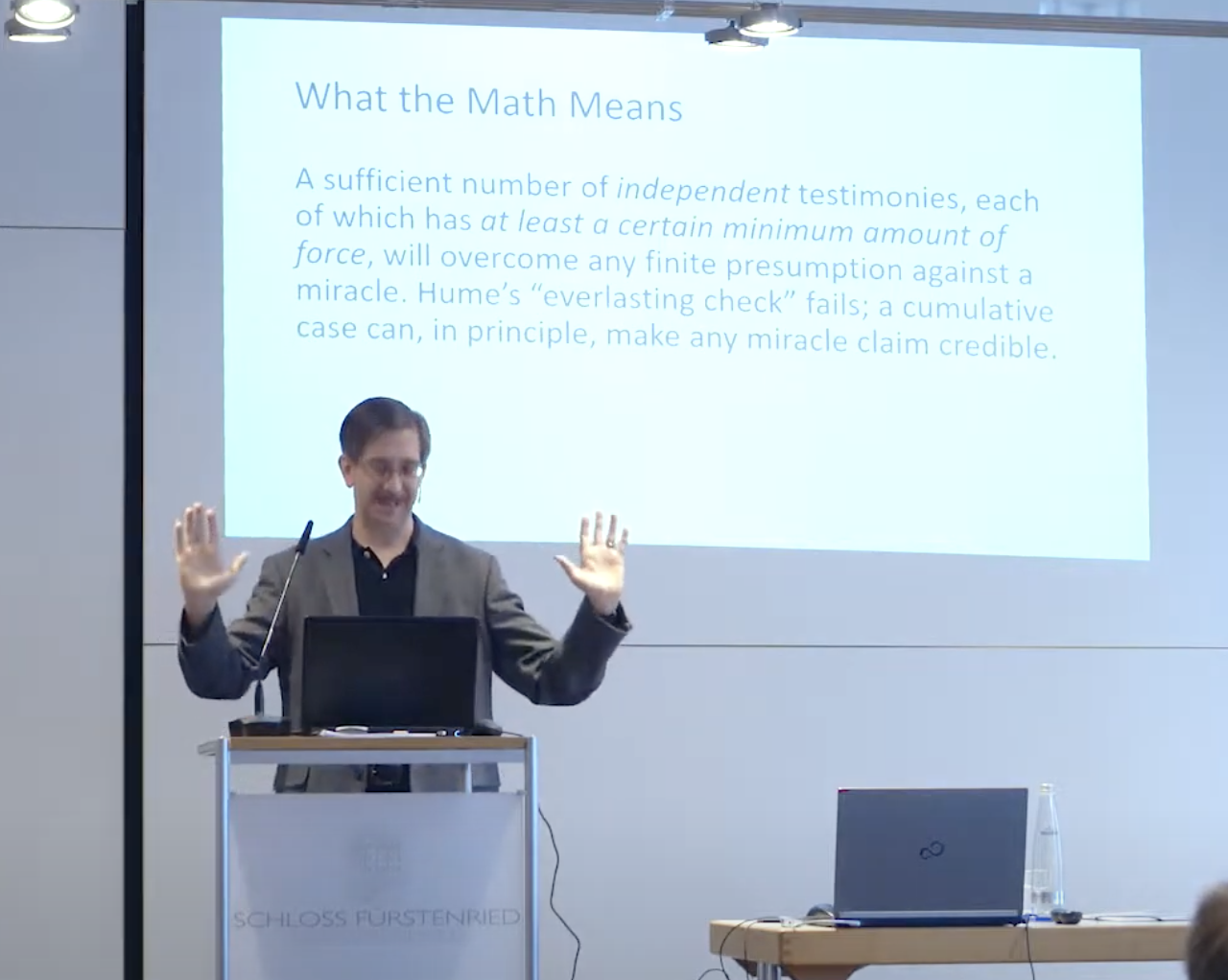

It relates to an idea about testimonies I've heard around, but clearly stated by Timothy McGrew:

What the Math Means - A sufficient number of independent testimonies, each of which has at least a certain minimum amount of force, will overcome any finite presumption against a miracle. Hume's "everlasting check" fails; a cumulative case can, in principle, make any miracle claim credible.

It's a mathematical fact that if we have all of the following...

then we can look at the posterior odds for the miracle,

<math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mtable columnalign="right left" columnspacing="0em" rowspacing="0.25em"><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mi>O</mi></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>≡</mo><mfrac><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>=</mo><mfrac><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>=</mo><munder><munder><mfrac><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>⋅</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>⋯</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>⋅</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>⋯</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>D</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac><mo stretchy="true">⏟</mo></munder><mtext>cumulative testimony</mtext></munder><mo>×</mo><munder><munder><mfrac><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac><mo stretchy="true">⏟</mo></munder><mtext>prior odds</mtext></munder></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr></mtable><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> \begin{aligned} O &\equiv \frac{P(M|D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_n)}{P(\bar{M}|D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_n)} \\ &=\frac{P(D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_n|M)P(M)}{P(D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_n|\bar{M})P(\bar{M})} \\ &=\underbrace{\frac{P(D_1|M)\cdot P(D_2|M) \cdots P(D_n|M)}{P(D_1|\bar{M})\cdot P(D_2|\bar{M}) \cdots P(D_n|\bar{M})}}_{\text{cumulative testimony}}\times \underbrace{\frac{P(M)}{P(\bar{M})}}_{\text{prior odds}} \\ \end{aligned} </annotation></semantics></math> and the cumulative testimony can, in principle (for sufficiently large <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>n</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">n</annotation></semantics></math>), overwhelm any small prior odds. The McGrews use this fact in their article The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, but definitely check out the 9-hour analysis of the problems with this article. (Part 1 of a summary can be found here).

Typical (and perfectly reasonable) responses to this are:

In this post, I want to explore point 2 above, that we do not have a claim itself, but instead we have someone making a claim. This provides one extra level of indirectness to the evidence. I want to discuss this, because I think this fact alone accounts for most of my own reticence in accepting extraordinary claims, why the methods of science work so well, and seems to show a naïveté in the apologists use of evidence. I also think this point is rarely addressed.

In E.T. Jaynes book on Probability Theory in Chapter 5 on peculiar uses of probability theory, he explores the idea of diverging probability assignments due to ones perspective on the source of the information. This idea motivated my particular approach here.

We have the proposition, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>M</mi><mo>≡</mo><mtext>a miracle occurred</mtext></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">M\equiv \text{a miracle occurred}</annotation></semantics></math>, for which we have a prior, <math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mtable columnalign="right left" columnspacing="0em" rowspacing="0.25em"><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>≡</mo><mi>m</mi></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>≡</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>m</mi></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr></mtable><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">\begin{aligned} P(M) &\equiv m\\ P(\bar{M}) &\equiv 1-m\\ \end{aligned}</annotation></semantics></math> Note, that for miracle here you can substitute any extraordinary claim. Our data consists not of extraordinary observations of the world but of a series of claims about such observations. This can include sources such as

For the sake of concreteness, I'll say that the data is <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>C</mi><mo>≡</mo><mtext>person X has made a claim of </mtext><mi>M</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">C \equiv \text{person X has made a claim of } M</annotation></semantics></math>.

For the sake of charity, we will assume that if a miracle has occurred, then the person would make that claim with certainty, <math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>C</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> P(C|M)=1 </annotation></semantics></math> Also for charity, we will ignore data that we'd expect under <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>M</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">M</annotation></semantics></math> but do not observe.

If the miracle did not occur, we might expect someone to make the claim that there was a miracle anyway. This could be from a simple mistake, someone who interprets the world, in general, in terms of divine-action (e.g. rain is caused by the Gods, etc...). It could be from outright lying. It could be from lack of proper observational controls, or lack of information. Any of these could lead someone to make a claim of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>M</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">M</annotation></semantics></math> even if its negation, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">\bar{M}</annotation></semantics></math>, is actually true. I simplify this to some constant probability, <math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>C</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>=</mo><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> P(C|\bar{M})=a </annotation></semantics></math> We can now write down with this simple model, the probability of a miracle given this data, <math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mtable columnalign="right left" columnspacing="0em" rowspacing="0.25em"><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>C</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>=</mo><mfrac><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>C</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>C</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>+</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>C</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mover accent="true"><mi>M</mi><mo>ˉ</mo></mover><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>=</mo><mfrac><mrow><mn>1</mn><mo>⋅</mo><mi>m</mi></mrow><mrow><mn>1</mn><mo>⋅</mo><mi>m</mi><mo>+</mo><mi>a</mi><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>m</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac><mo>=</mo><mfrac><mi>m</mi><mrow><mi>m</mi><mo>+</mo><mi>a</mi><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>m</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr></mtable><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> \begin{aligned} P(M|C) &= \frac{P(C|M)P(M)}{P(C|M)P(M)+P(C|\bar{M})P(\bar{M})} \\ &=\frac{1\cdot m}{1\cdot m + a\cdot (1-m)} = \frac{m}{m+a\cdot(1-m)} \end{aligned} </annotation></semantics></math> It's good to pause to see if this form makes sense. If <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>0</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=0</annotation></semantics></math>, which means that if there is no miracle, person <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>X</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">X</annotation></semantics></math> will never make the claim that there is one. This leads to <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>C</mi><msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>0</mn></mrow></msub><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">P(M|C)_{a=0} = 1</annotation></semantics></math> which is what is expected -- the claim of a miracle can't be mistaken. What if person <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>X</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">X</annotation></semantics></math> always reports a miracle, even if there isn't one? In that case <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=1</annotation></semantics></math> and we get <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><mi>C</mi><msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow></msub><mo>=</mo><mi>m</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">P(M|C)_{a=1} = m</annotation></semantics></math> which is our prior probability for a miracle. Essentially, this person with <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=1</annotation></semantics></math> gives no useful information -- they are the proverbial boy who cried miracle. No new information means that our probabilities do not change and we are left with our original prior probability.

We can think of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math> as a measure of the reliability (or rather unreliability) of the source, with <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>0</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=0</annotation></semantics></math> being completely reliable and <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=1</annotation></semantics></math> being (nearly) unreliable. I say "nearly" because we are still assuming that person <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>X</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">X</annotation></semantics></math> reliably communicates a miracle if it does occur.

One thing to note about our charitable choices in this model is that that the probability can never go lower than the initial prior. This is clearly wrong, because one can potentially have disconfirming evidence for a miracle, but we are not considering this here. Thus, at the outset, this model has a pro-miracle bias built in. Even with this bias it will become clear how we can counter miracle claims by exploring the scientific process in a bit more detail below. First, we reproduce the McGrew observation above using this model, by accumulating multiple independent claims, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>0</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mi>n</mi></msub></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">C_0, C_1, C_2, \ldots, C_n</annotation></semantics></math>. Following the process above (checking with WolframAlpha) we get

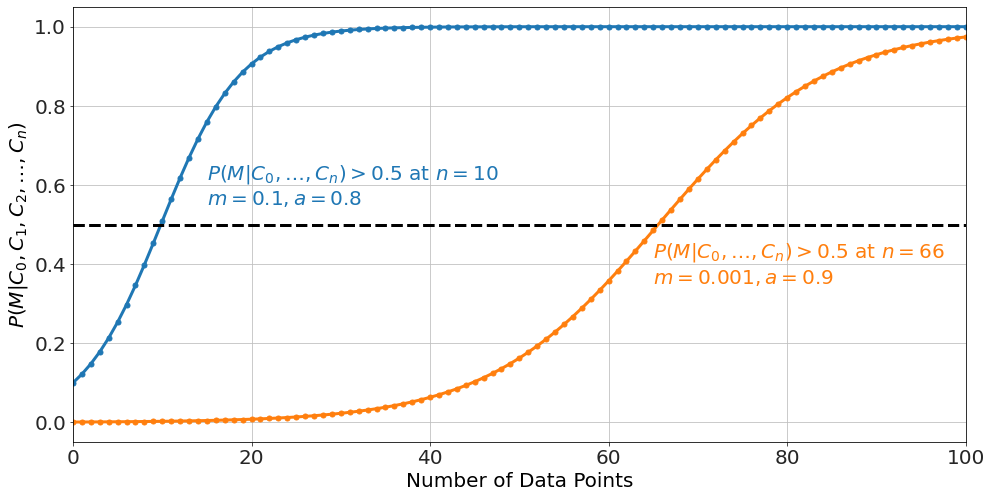

<math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mtable columnalign="right left" columnspacing="0em" rowspacing="0.25em"><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>0</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>=</mo><mfrac><mi>m</mi><mrow><mi>m</mi><mo>+</mo><msup><mi>a</mi><mi>n</mi></msup><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>m</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr></mtable><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> \begin{aligned} P(M|C_0, C_1, C_2, \ldots, C_n) &= \frac{m}{m+a^n\cdot(1-m)} \end{aligned} </annotation></semantics></math> A couple of examples would look like

One can show that, with a high enough <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>n</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">n</annotation></semantics></math>, even a very low prior (<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>m</mi><mo>≪</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">m \ll 1</annotation></semantics></math>) and a really unreliable source (<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>∼</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a \sim 1</annotation></semantics></math>) you can recover the probability of the miracle. In the example above, I show for a slightly low prior for miracle (<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>m</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>0.1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">m=0.1</annotation></semantics></math>) and a marginally unreliable source (<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>0.8</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=0.8</annotation></semantics></math>) we recover the probability of a miracle (<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>0</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>></mo><mn>0.5</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">P(M|C_0, \ldots, C_n)>0.5</annotation></semantics></math>) in about 10 data points whereas with a lower prior by a factor of 100 and a more unreliable source, it takes <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>n</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>66</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">n=66</annotation></semantics></math> points. One can question whether the claims-data used to support miracles rise to this number (I don't think it does), but that will not be my main point here.

The process of data and model comparison doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's against a backdrop of science demonstrating that many (all?) of the claims for miracles and most extraordinary claims (e.g. UFOs, alien abductions, homeopathy, etc...) have been shown to be false or at best unsubstantiated. It is my personal experience that none of the miracle claims that have been presented to me withstand even the slightest level of scrutiny. There's a very long discussion on the best cases here with the same result -- one problem after another. How does this affect the model above? Imagine the following process:

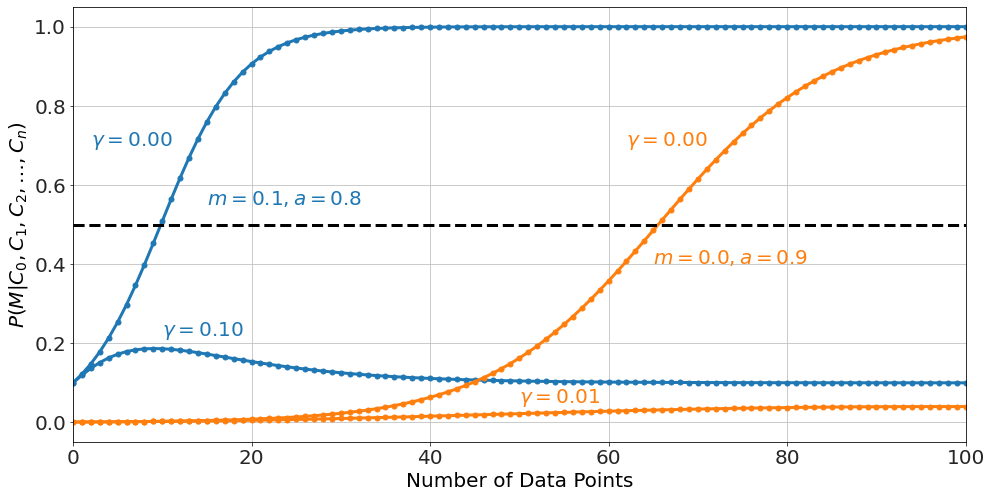

which pretty much describes my personal experience with the evidence for miracles (and most extraordinary claims). Each time a claim is put up, and I investigate it, I find it lacking -- usually in pretty mundane and straightforward ways. Either the claim is completely debunked or at a minimum shown to be not reliable. What this process does is change how reliable the sources are, so that next time, similar claims might be less likely. In the model, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math> is pushed toward the value of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">1</annotation></semantics></math> each time a claim is dispensed with. Mathematically, a simple way to accomplish this is to add to <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math> some fraction, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>γ</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">\gamma</annotation></semantics></math>, of the remaining distance between <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">1</annotation></semantics></math> and the current value of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math>. In this way, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math> is pushed toward <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">1</annotation></semantics></math> but will never reach or exceed it.

<math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>→</mo><mi>a</mi><mo>+</mo><mi>γ</mi><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>a</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> a \rightarrow a+\gamma\cdot (1-a) </annotation></semantics></math> thus the source-reliability, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math>, is no longer a constant but depends on how many (<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>n</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">n</annotation></semantics></math>) claims have been presented (and dispensed with). We can find <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a</annotation></semantics></math> as a function of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>n</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">n</annotation></semantics></math>,

<math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>n</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>=</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>a</mi><mn>0</mn></msub><mo>+</mo><mi>γ</mi><mo>−</mo><mn>1</mn><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>γ</mi><msup><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mrow><mi>n</mi><mo>−</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow></msup><mo>+</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> a(n) = (a_0 + \gamma -1)\cdot (1-\gamma)^{n-1}+1 </annotation></semantics></math> where <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><msub><mi>a</mi><mn>0</mn></msub></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a_0</annotation></semantics></math> is the initial assessment of the reliability of the source of the claims. A quick pause to see that this makes sense: if <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>γ</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>0</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">\gamma=0</annotation></semantics></math> there is no change to the reliability of the claims, and we have our original value <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>n</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>=</mo><msub><mi>a</mi><mn>0</mn></msub></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a(n)=a_0</annotation></semantics></math>. If <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>γ</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">\gamma=1</annotation></semantics></math> then even after the first claim, the source becomes completely unreliable, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>=</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a=1</annotation></semantics></math>.

This new process gives us a messier posterior for the miracle,

<math display="block" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mtable columnalign="right left" columnspacing="0em" rowspacing="0.25em"><mtr><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mi>P</mi><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mi>M</mi><mi mathvariant="normal">∣</mi><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>0</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>1</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mn>2</mn></msub><mo separator="true">,</mo><mo>…</mo><mo separator="true">,</mo><msub><mi>C</mi><mi>n</mi></msub><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mstyle></mtd><mtd><mstyle displaystyle="true" scriptlevel="0"><mrow><mrow></mrow><mo>=</mo><mfrac><mi>m</mi><mrow><mi>m</mi><mo>+</mo><msup><mrow><mo fence="true">(</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><msub><mi>a</mi><mn>0</mn></msub><mo>+</mo><mi>γ</mi><mo>−</mo><mn>1</mn><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>γ</mi><msup><mo stretchy="false">)</mo><mrow><mi>n</mi><mo>−</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow></msup><mo>+</mo><mn>1</mn><mo fence="true">)</mo></mrow><mi>n</mi></msup><mo>⋅</mo><mo stretchy="false">(</mo><mn>1</mn><mo>−</mo><mi>m</mi><mo stretchy="false">)</mo></mrow></mfrac></mrow></mstyle></mtd></mtr></mtable><annotation encoding="application/x-tex"> \begin{aligned} P(M|C_0, C_1, C_2, \ldots, C_n) &= \frac{m}{m+\left((a_0 + \gamma -1)\cdot (1-\gamma)^{n-1}+1\right)^n\cdot(1-m)} \end{aligned} </annotation></semantics></math> But easy to look at numerically,

We can see the effect of claims being shown to be unreliable can make further testimony less reliable, even in a model which has a definitively pro-miracle bias. One can see in the curves on the left that the initial claims increase the probability of a miracle, but as they get debunked that initial increase in confidence is erased, and further testimony reduces the probability of claims back to the prior.

When asked the question raised by McLatchie,

I would have to say that new testimony does not raise my probability for a miracle, mostly because all prior attempts to do so have been debunked or at best shown to be profoundly unreliable. This lowers my credence in the sources, even if I don't have time to investigate in detail the next new claim. Am I being hyper-skeptical? I don't think so -- I'm simply adjusting my beliefs to the evidence, and that evidence is that miracle claims have not met their burden of proof. How could this problem be addressed for me? In modern settings, having randomized-controlled studies of miracles would be the best -- because those claims that use this process have shown themselves to be reliable, and thus <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>→</mo><mn>0</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a\rightarrow 0</annotation></semantics></math> in the model above. Given modern miracle claims, and their issues, I don't think that any ancient source could convince me of miracles -- their reliability on matters of the physical, chemical, and biological world has been shown to be terrible, thus <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>a</mi><mo>→</mo><mn>1</mn></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">a\rightarrow 1</annotation></semantics></math>.

Although this model is a simplification, it is useful to see that the adjustment of probabilities needs to be taken with care and that unintuitive and non-monotonic effects can easily occur (you can see another non-monotonic effect with the high-low-nines deck example shown here). Even if for a single data point, the probability of a model increases, the same can't be said of an accumulation of data points unless one is sure that the simplifying assumptions are correct -- and they never are.