Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In #science

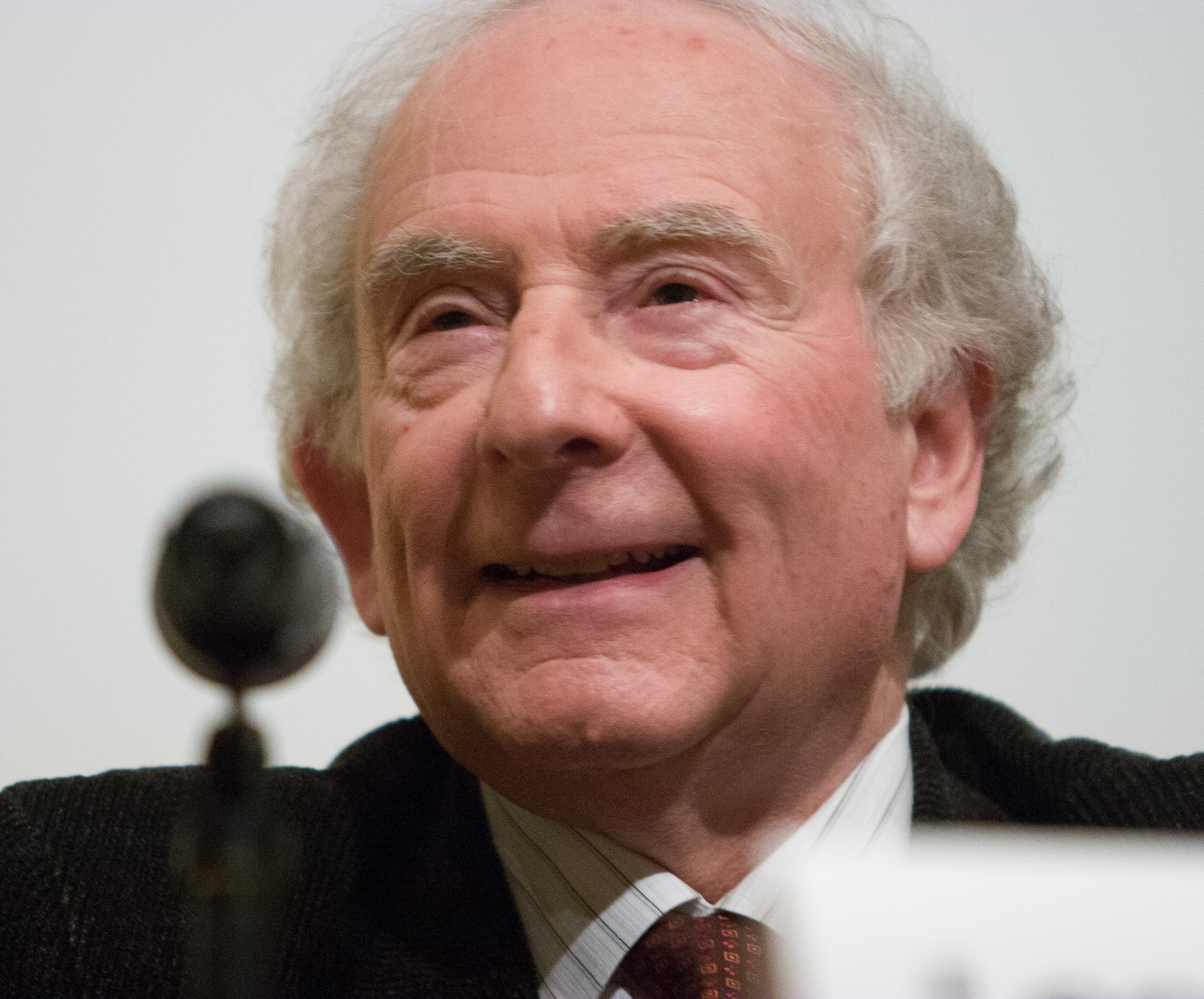

My mentor and friend Leon Cooper has died at the age of 94. I am still grappling with this news, hitting me harder than I expected. However, why wouldn't I expect to be shaken by this news?

I first met Leon Cooper at Brown University in 1994, me still a new graduate student in Physics in my second semester. I had come to Brown to either study astrophysics or to study with Leon Cooper who was working on models of the brain. He had won the Nobel Prize for his work on Superconductivity, and was working now on computational neuroscience -- a field that basically didn't exist when he started to work on it.

I was always interested in the "big questions" and both astrophysics and neuroscience spoke to these questions. I interviewed with another graduate student in Leon Cooper's lab at the time, Mike Perrone, who put me on a project during my second semester -- presumably to see if I could hack it in the lab. I did contribute to his project, and presented my work at a conference. Leon Cooper then offered me a summer stipend where I would work on understanding some of the recent work of Charles Law and Harel Shouval, who had been doing simulations of synaptic plasticity in the visual system. That was 1994 -- 30 years ago. This semester, now 2024, I submitted for a conference presentation using some of the same models I was introduced to in 1994. This speaks to the strength of the BCM synaptic plasticity model (named after the 1982 authors Bienenstock, Cooper, and Munro) and to the influence Leon Cooper has had both in the field of neuroscience and my own professional life.

The Brown University Physics Department had a "qualifying exam" the September of one's second year as a graduate student. It consisted of a 2-day written exam followed by a possible oral exam. If you scored above a 70 on the written exam, you'd pass outright. If you got between a 60 and a 70 you'd have an oral exam. Below a 60, you'd fail and have another chance six months later. I got a 55 on the exam. I was able to argue for 5 more points, due to questions being unclear or me approaching problems in a different way than expected. After the new points, I had achieved a 60 on the qualifying exam -- the minimum for an oral exam. A few days later, I have my oral exam with three professors, including Leon Cooper. The stakes were whether I could stay at Brown University for physics. I don't remember a lot about that exam, other than that it was one and a half hours, I blanked on some questions, and felt confident on others. I distinctly recall Leon's questioning style -- one that I have adopted whenever I give oral exams. He would ask a super-easy question, one where to get it wrong really should result in a failing grade. Then he'd add a small complication, and ask a follow-up question. After several of these step-ups, until you couldn't answer the question, he had a very good measure of what you knew while at the same time removing the effect of being nervous or blanking on a topic momentarily. This process of starting easy, and moving up in small steps, was a brilliant measurement method for determining someone's aptitude in a topic. It was one of many things that Leon did gently and brilliantly and that I have tried to emulate since.

After the exam, I went up to the lab wondering if I would be able to stay, not at all confident in my performance. I sat down, and wrote out one of the answers I had blanked on. I still tell my students that I can more easily write things on paper than in front of a whiteboard. Leon came up to tell me the result of the discussion, and he said that the consensus was that I was borderline and that if he decided to pass me, I'd be "his problem now", smiling and lightly laughing as he did when bemused. He did pass me which has affected my entire life trajectory since.

In a letter I wrote for Leon's 80th birthday I told him "although I know that I am, at best, a mediocre physicist you have always made me feel as if I were much better." It was always clear that Leon Cooper had a way of looking at the world that was far deeper and clearer than anything I could approach. In neuroscience seminars, I watched as he listened to a graduate student or postdoc present their research and then ask them such a penetrating question that they were taken aback. He was able to slice through all of the complexities that biologists are trained to focus on and find a problem or solution about their research question that they had never considered. It was a skill of making things as "simple as possible but no simpler", a la Einstein, and Leon had an ability to do this across the multiple disciplines of physics and biology that was worthy of two Nobel Prizes, in my opinion. Yet, in our personal interactions, he never made me feel like I was in any way inferior to him.

Some of my fondest memories are from our weekly meetings, which lasted until February 2020, stopping due to Covid. Even when he wasn't as active in research, he was always interested to hear the latest work that I was doing. Given my teaching and service obligations, my research has been somewhat glacial on certain topics, but Leon was always interested. We spoke about the interpretation of quantum mechanics, a topic he loved and that I was also interested in but had far less aptitude than he. We also had a shared interest in the methods of teaching different topics in physics. I made an audiobook of the recordings of his class "Physics: Structure and Meaning". Ironically, I hadn't listened to it in quite a while, but had picked it up this week again before I had heard the news of his passing. I love Leon's approach to teaching of telling historical anecdotes, and leading the students through the thought process the scientists had as they developed the current theories. He did this, rather than just provide them the answers, to give them a connection to the material that I don't think any textbook or YouTube video could rival. Leon Cooper was the quintessential teacher, and was in a unique position to inform his teaching with his experience unraveling some of the fundamental mysteries in physics earning him his Nobel Prize.

It is no exaggeration to say that Leon Cooper has been the most important person to my professional career, always supportive even when I knew that I was not performing up to the potential I could have. I have always striven to be like him -- clear in his vision of how the universe works, passionate about teaching, always able to see through to the essential important issues whether that was in physics or biology, and gentle to the core. I never heard him raise his voice in the 30 years I've known him, yet he was always clear in expressing when he disagreed with a point.

Like many things, our weekly meetings were disrupted by Covid and then Leon was ill for a while. I met with him once at his house in 2021. I regret not making it a priority to visit more often. I wish I could have communicated to him how much he has meant top me, and still means to me and that so much of the way I think and work and appreciate this life comes from him. I was already missing Leon, and knowing that I won't have any more discussions over coffee with him breaks my heart. I will always be thankful for the happy accident that brought us together and for his wonderful presence in my life. I will always remember him, and with the wonders of modern technology, I get to hear his teaching voice anytime I want to.

I will always remember Leon and the influence he had in my life. With Leon Cooper, thus passes one of the most amazing humans that has ever lived, and I have been blessed to have crossed part of his path on my own journey, for which I am eternally thankful. Farewell Leon.