Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In #math

I realized that I don't have a blog post about my favorite simple probability example, the High-Low Deck Game. I've written about it in Statistical Inference for Everyone but I think it is useful to have it written here, demonstrate a notational difference from many statistics textbooks, and talk about some of the interesting conclusions.

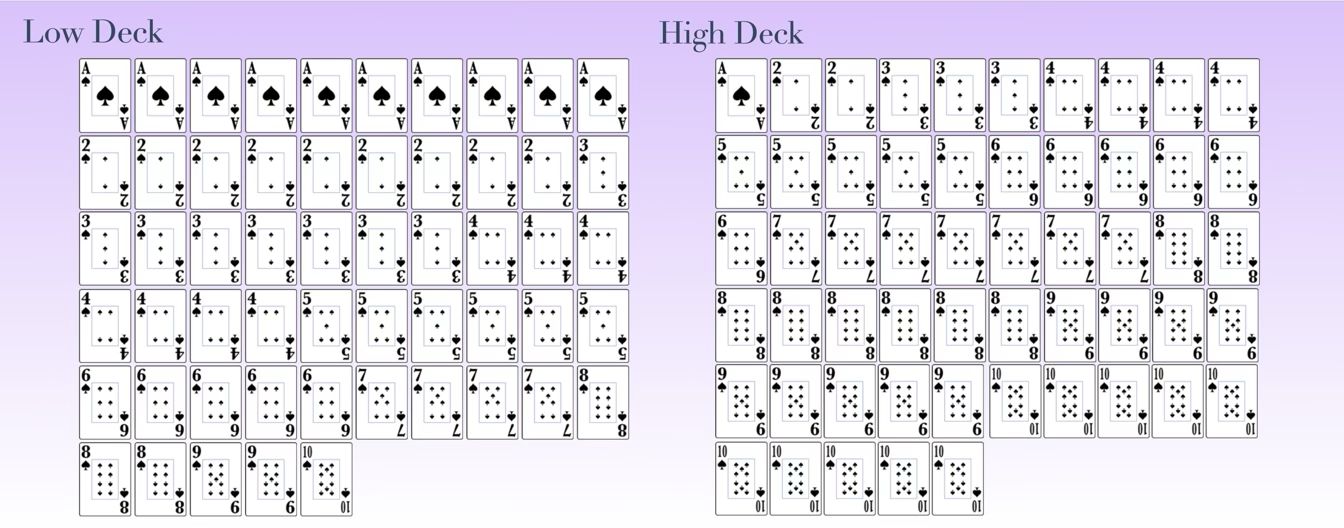

We start with two atypical decks of cards called the Low Deck and the High Deck,

You'll notice that both decks have 55 cards, and that the Low Deck contains many more low cards while the High Deck contains many more high cards. The game is played like,

The goal is to determine which of the two decks (Low or High) you are in fact holding in your hand. In practice, we are calculating the probability we are holding the Low Deck given the data, \(P(L|\text{data})\), and the High Deck given the data, \(P(H|\text{data})\).

If you're impatient, you can jump down to the fInal result

We start by exploring our intuitions, before we do anything mathematically. Thus, we are in a position to check to see if the math is reasonable before we use the same math in areas where our intuition is not as strong. Imagine we draw only one card, and it is a 9. Intuition suggests that this constitutes reasonably strong evidence toward the belief that we're holding the High Deck. If we then (as the procedure states) place the 9 back in the deck, reshuffle, and then draw a 7 we can be more strongly convinced that we are holding the High Deck. Repeating the reshuffle, and then drawing a 3 would make us a little less confident in this conclusion, but still quite certain. In this way we can sense how drawing different cards pushes our belief around, depending on how often that card comes up in the different decks.

Before we take any data, we need to quantify our state of knowledge concerning all the models that we are considering. In this case it is quite simple, because there are two models (High Deck and Low Deck), and we have been given no information about whether either is more common. With no such information, it is equivalent to a coin flip - we assign equal probabilities to both models before we see data, also known as the prior probabilities.

Surely this assessment will change after we see data, but that is the rest of the problem.

Although our ultimate goal is to infer the type of deck from the cards that we draw from it, we can start looking at an easier part of this question. This serves as a first step toward the more challenging, and interesting goal. That question is the following, What is the probability of drawing a 9, given that we know that we're holding the High Deck? This question is written mathematically as

where \({\rm data}=9\) means that we have observed (i.e. drawn) one 9. This question is "easy" in the sense that it is simply related to the properties of the High Deck: the number of 9's and total number of cards. If you know that you have the High Deck, then you know there are nine 9's in that deck out of 55 cards. Thus, we have the probability of drawing one 9, given that we are holding the High Deck,

We give this the name likelihood, and is simply the probability that the data could be the result of a known model.

Now that we have our intuition, and we have the likelihoods, we can address the math. The two models are:

and the initial data is

We are look for the two probabilities:

which are related to the prior and the likelihood via Bayes' Rule

To calculate actual numbers, we apply the Bayes' Recipe to this problem,

From which we can conclude that drawing a 9 does indeed constitute reasonably strong evidence toward the belief that we're holding the High Deck - the probability of us holding the High Deck started at 0.5 and given the data is now 0.82.

So, when we draw a 7 next (after reshuffling), our intuition suggests that we'd be more confident that we're holding the High Deck. Repeating our recipe we have

The two models are:

and data is

We are looking for the two probabilities:

which are related to the prior and the likelihood via Bayes' Rule:

To calculate actual numbers, we apply the Bayes' recipe to this problem,

In the above example, we started with a prior probability of holding the High Deck at \(P(H)=0.5\), because we had no information other than that there were two possibilities. We then observed a 9, and updated the probability to 0.82, and then observed a 7, and further updated the probability to 0.889 - making it more likely that we were holding the High Deck.

One of the basic tenets of probability theory is that if there is more than one way to arrive at an answer, one should arrive at the same answer. In the above, we calculated the probability of holding the High Deck given the observed data

and prior information

This is entirely identical to having the following prior information:

and observed data:

As such, these two problems must yield identical answers.

Mathematically, we apply the Bayes' recipe, but with the different prior information

yielding the same result.

In other words our updated probabilities from the first draw can be seen as our prior probabilities for the subsequent draws. Thus, Bayes' Rule describes how we update our knowledge with new evidence. We can calculate these probabilities all at once with all the data, or step-by-step as the data come in -- the results must be identical.

This is where the notation we've been following really shines. In other formulations, such as the odds form of Bayes theorem, moving beyond two models/hypotheses is cumbersome at best and impossible at worst. We'll slowly walk into the multiple models, but for now let's assume we are either holding the High or Low Deck, and we observe this data:

Performing the same calculations, we get

which is fantastically on the side of the high deck.

What about this data?

Blindly following the procedure above gets us \(P(H|{\rm data})=0.999999999841\).

We might start getting suspicious in this situation, because even though the data of a string of 9's is highly expected on the High Deck, compared to the Low Deck, we should start seeing other cards as well. We might start considering that the information that we've been given is incorrect -- that there are more decks than the High and the Low, or someone isn't actually reshuffling properly. These are other models that can explain the data, but would have to be a-priori much lower for us to not have considered them before now. As an example, let's introduce a third model -- the Nines Deck -- and follow the procedure again. We'll generalize to an unspecified number of \(m\) 9's, so that we can easily explore all possibilities.

What is interesting here is that once we admit that there are many possible models we could consider, we realize that we have these models in our head all the time, or we construct them as we need them. Every model comparison is a multiple model comparison, with most of the models with very low prior probabilities that our brain naturally suppresses until needed. Mathematically, we need to unsuppress them as needed, but their probability will have to be rescued with data.

Let's say that we assign the prior probability for the Nines deck to be a one in a million. To make all the prior probabilities add up to 1, the prior probabilities for the High and Low Deck must be a little less than 0.5. After that, we simply apply the Bayes' Recipe as before

1. Specify the prior probabilities for the models being considered

2. Write the top of Bayes' Rule for all models being considered

3. Put in the likelihood and prior values

4. Add these values for all models

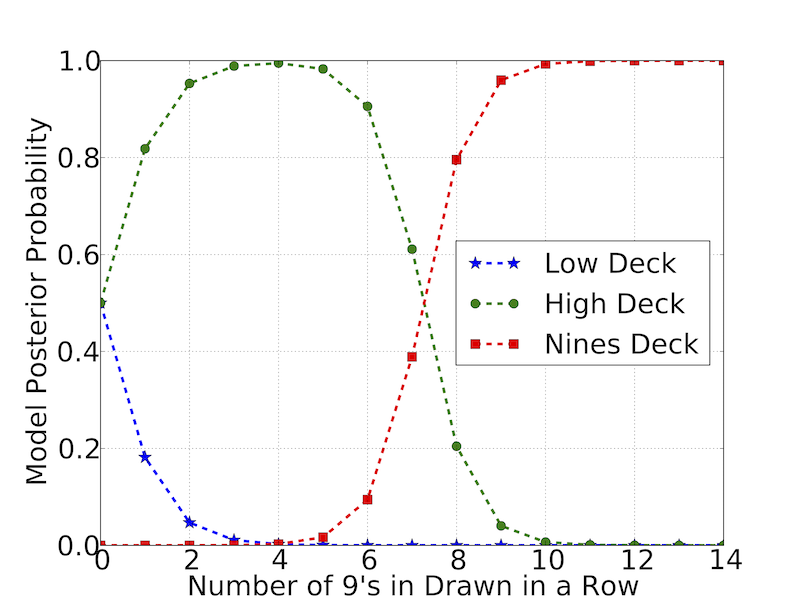

5. Divide each of the values by this sum, \(T\), to get the final probabilities. This step is easiest done in a table or, even better, a picture, as in the following.

There are a number of interesting observations about this figure. When \(m=0\), we get the (nearly) 50/50 split between High and Low decks -- before we draw any data, this is the prior. As we draw 9's, our confidence that we're holding the High Deck goes up, at the expense of our confidence that we're holding the Low Deck. At a certain point (around six 9's in our example), our confidence in the High Deck starts to drop. We become more confident that something odd is happening, and our previously ignored model of the Nines deck becomes more likely. Eventually, this new model is the one in which we are the most confident.

This is an example of a non-monotonic probability change -- drawing the same data sometimes increases the probability of a model and sometimes decreases that very same model. It all depends on the alternatives being considered. I suspect that the non-monotonic effect only occurs when one considers more than two models. As such, the standard way of presenting Bayesian analysis -- either using the full equation, or by looking at odds ratios -- never see this effect and the resulting analysis can be somewhat naive.

The non-monotonic effect is also why, when a psychic demonstrates some amazing feat of apparent mind-reading, they still won't be believed immediately. This is because many rare and unconsidered explanations will rise from low prior status to dominate. These low prior models still have a higher prior value than the ESP model, but are low enough to not be considered immediately. The next step would be to modify the data collection process to potentially eliminate them. In other words, to design an experiment to rule out these alternate explanations. This is the process of science -- designing experiments to make these low prior models less likely in the hope of increasing the probability of the model under consideration.