Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In this YouTube episode, Bad Apologetics Ep 18 - Bayes Machine goes BRRRRRRRRR I join Nathan Ormond, Kamil Gregor, and James Fodor to discuss Timothy and Lydia McGrew's article in The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology entitled "Chapter 11 - The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth".

It's 9 hours long, but I am only on for the first 7 hours. This isn't a complete log of everything said, but I tried to include the main points. I also started with a transcript, and edited it for clarity (e.g. removing ums, and repetition) but there may still be some weird typos from the computer generated transcript that I didn't catch. I will try to quote Nathan, James, Kamil and myself if it comes from the episode. All other text is mine, commentary either at the time or sometime afterward.

The parts of this document are here:

And the link for the full video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/yeCBpO7pSRM

The main issues are:

Kamil: this is actually one of the strongest reasons for me to doubt the eyewitness testimony behind the Gospels especially if you think that the Gospels were written in the genre of Greco-Roman historical biography. [...] if you think that, then it's actually really, really unexpected that the authors of the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of Matthew, for example, don't explicitly say they are based on eyewitness testimony. Because eyewitness testimony was very highly valued in ancient historigrapphy and I find it consistently over and over again. When it's the case that the historian in question actually had eyewitness testimony available, that they were the eyewitnesses themselves or they had access to eyewitness testimony, they say that explicitly in the text. It is actually very, very difficult to find instances where it's the case that they had access to eyewitnesses but they don't actually proactively disclose it. [...] I would absolutely expect Mark to say "this account is based on the memory of Apostle Peter". I would absolutely expect, for example, the Gospel of Matthew to say, I Matthew, The Apostle was called by Jesus or something like that because that's exactly what we observe over and over again in other historical accounts

This is an example of data which is expected on the hypothesis of eyewitness testimony, which is seemingly required for the McGrews to make any headway in their case to support the Resurrection. This data is also simply not dealt with, or written off as an argument from silence (which it isn't).

Kamil: So this is like a one piece of evidence that massively goes against the hypothesis of eyewitness testimony that actually, for me, the strength of that evidence is so overwhelming that it actually overcomes all of the early Christian attestation to the authorship

James: We're about to get to looking at the the data that we're then going to compare explanations against . And what we'll see is that when they reject or argue against non resurrection explanations, they are happy to pick literally any detail from the gospels that suits their purpose. Very specific, very particular, minute sometimes detail. And the question would be, "Well, why should we accept that that is the case?" And it seems to me that we're going to have to go beyond a general reliability to get to that. We're going to actually have to go to like, basically, this was written not just by an eyewitness, but someone with a really good memory and got all of the details down. So by feeling free to appeal to all of these details, they're actually setting up a very high standard for themselves in terms of how confident can we be in these details. So to put it another way, it's very much not a minimal facts approach. We'll see the sort of details that they're appealing to and like it really does, then heavily rely on how reliable we think all of these details are.

Here is the first of many examples where they argue against a claim by appealing to the fact that it is intrinsically highly improbable -- which is a prior, the part of the calculation that they are definitely not talking about with respect to theists claims. As Bart Ehrman pointed out, it might be improbable -- but it is more probable than a miracle!

Kamil: Yeah, but but it's always the case with minimal effects, right? Like you start by saying, this is just a list of minimal facts. And yes, that's true. 30 minutes later. It's no really, there were people who thought they saw Jesus eating a piece of fish in front of them. So how do you explain that a naturalism, right? They could not have hallucinated it because it was tactile and hallucinations are not like interpersonal and tactile.

Brian: I always find it telling that the list of minimal facts never seems to be an agreement from one apologist to another.

Kamil: The swoon hypothesis is specifically aimed against Muslims, right? Because in the Koran, it says that Jesus didn't really die, but how they argue against it actually doesn't have any force against what the Muslims believe. Because in the Koran, it says that Jesus didn't die, but it looked like he did. So like Allah made it look like he died, which is obviously completely consistent with the historical account, right?

Nathan: so when they compare the evidence, they say, how do we expect the evidence to look given "not the resurrection", right? Well, that would be exactly the same in that case because the evidence would look exactly the same, so it shouldn't do anything to that numerator denominator distinction. The ratio should just remain, but they don't do that.

And note again, that they criticize the swoon hypothesis because it is "intrinsically improbable", which is the prior they don't want to have to address on their own view

Nathan: They say one of the problems here for the skeptic who goes with this and I don't think any of us do go with the swoon theory. But he says, for example, you've got to "dismiss John's account of the spear wound as inauthentic". Well, that theory actually coheres with other details like, for example, the mistranslation of prophetic fulfillment. It might be the case that they were reading the Septuagint to figure out what happened about Jesus life. I think like that coheres quite nicely.

Nathan: they go on to talk about this John Dominic Crossan, something that his theory and then they say, you know, that his "radical position", well everything that they're saying is radically out of line with New Testament scholarship. But it's again, just not the type of language that you really expect from an academic volume.

James: Look, when they say something, it's an "inference". It's an "argument". It's "based on evidence", "growing body of evidence" when someone else says it. Oh, it's just a "guess". It's a "mere extrapolation". It's a "radical position". It's just fluff. Like, there's no actual distinction here between what different people are doing. It's just whether they agree with that or they don't agree with that.

Kamil: I'd also also like that there is no shortage of people who believe that a person was raised from the dead, even though that person has a known burial location that supposedly contains the body. it demonstrates two things. First of all, that people who hold the belief that the person was raised are not interested in actually confirming that with physical evidence. They don't sneak up into the graveyard and dig up the grave to see if it has a body in it. Probably exactly for the reasons like if they were actually presented with the body they'd probably dismiss it. And second of all, the other people who don't share that belief are not interested in debunking it by exhuming the person and showing the body because it's more important for them not to disturb the burial customs of the person than to debunk that specific claim.

You know, there is the famous Jewish rabbi (Menachem Mendel Schneerson) who claims to be a messiah. And apparently, they are still people who believe that he was resurrected, even though there is a zero empirical evidence for it. He actually has a known burial location. And also what's very important to realize is that even the people in the position of leadership in that specific sect of Judaism denied that claim. There were actual leaders who said, "no, he wasn't raised." But despite all of that, yeah, there are still adherents.

This point, to me, shatters the entire apologetic edifice around the Resurrection. To have a parallel case like this, where all of the boxes are checked for belief, with the only difference between this rabbi and Jesus is that we have fewer pieces of evidence concerning Jesus.

James: The point that I wanted to make with that example is though, that to say that" oh well, they must have had really good evidence, right? And their opponents mustn't, if anything, good to say, because if they did, then that would have dissuaded the people from from believing it." But we've just given a couple of examples. I cite a number more in my book about irrational belief persistence. There's so many cases of this that the claim that they would have stopped believing unless they had good evidence, there's just no reason for thinking that -- it's just assertion. There's so much evidence that that isn't the case. That's just not how people work in these contexts.

James: \(W\) Is women's testimony, \(D\) is for the disciples, which includes seeing and being willing to die and \(P\) is for the conversion of Paul. So these are the three main facts that they wanting to put in their sort of Bayesian calculation, And they're going to say that these facts here are overwhelmingly more likely under the resurrection hypothesis than other than not-resurrection hypothesis. So that's what the next few sections are going to be is going through each of these in turn.

Brian: Make sure every time you see this, instead of saying, you know, the women who claim to have found the tomb empty or there were disciples who claim to have appearances of the resurrection, say instead that that we have texts that say that there are women who claim to have found the empty tomb, that we have texts that say that there were post resurrection appearances of Jesus. The data is not the claim itself, it's not the story, it's the fact that we have a text that has the story.

Nathan: But here's one point to focus on. So they're going to appeal a lot to consensus in New Testament scholarship. They're going to say, In a survey of recent New Testament scholarship, Gary Habemus has documented the interesting fact that a notable majority, approximately 75 percent of scholars writing on the subject during the thirty years from 1975 to 2005 agree that Jesus tomb was in fact found empty.

James: they have just been telling us at some length how unreliable the methods that most scholars who analyze this, like the critical scholars, the people that they don't like, right? So apparently, we shouldn't believe anything that they say -- we should discount them, it's not really reliable. But now we're being told that the fact that most scholars, including this big group that we shouldn't listen to, think that something is true is a reason for believing it. They do this in other cases as well later on. Again, it's eating a cake and having it to. Look, if we disagree with them, they're unreliable. But when they agree with us, we'll say, Oh, you know, this consensus of scholarship, you know, most scholars agree with us here.

Kamil: Also, this statement is factually false. Habermas has published this number in the literature, but he doesn't say that 75 percent of scholar agree that Jesus's empty tomb is a fact. What he says specifically, is that approximately 75 percent of scholars think that at least one of the arguments for the empty tomb has force or something like that. My hypothesis is that he phrases it like this so that it's not that explicit claim. He's not reporting the number of scholars who are convinced of the empty tomb to fudge the numbers. Because he could count in those 75 percent even scholars who are, for example, agnostic about it as long as they think that at least one of the arguments for the empty tomb is an interesting argument to look at.

Kamil: I want to highlight this because here we see Lydia McGrew and Timothy McGrew reporting something other than what Gary Habermas reported. So here we have an example of how information is distorted, when is what is retold like. The meaning is different and it's substantively different. It's very important that the difference is not superficial. It's actually very, very important. There's a distortion of information that took place, even though we live in an environment where it's super easy and super convenient to get access to the text exactly as Gary Habermas wrote it. Gary Habermas is still alive and I'm sure he would be able to answer any questions if they sent him an email. Now, imagine how much worse these kinds of distortions were in a society where people were not literate, they couldn't easily get a handle of the people who made the various claims that they are reporting. They did not have instant access to texts as they were originally written.

Brian: It's clear the McGraw's are right here because I don't hear Gary Habermas contradicting this and he'd be in a position to contradict this if it were actually incorrect.

James: there is a massive confusion between textual independence and independence of the witnesses that allegedly underpin that text. So it could be the case that I mean, obviously the Synoptics are not textual independent, but suppose that John and the Synoptics are textually independent. And what I mean by that is that they sat down to write their text separately from each other that hadn't seen. Obviously, Mark hadn't seen John, but John hadn't seen the Synoptics before (hypothetically). That would make them textually independent. But even if even if all four were textually independent, somehow that wouldn't make them independent of the underlying eyewitness testimony, which was based on a set of people who mostly experienced Jesus together, who talked to each other, as it says, even in the Gospels, and who allegedly came up with a creed that stated in propositional form some of the key beliefs that they had and passed it on to Paul and then that was disseminated in the other church. That is not what independent testimony looks like.

Kamil: So you're saying something like the group appearances are actually evidence against the resurrection because like, it would be much more powerful if Jesus appears to people like individuals independent of each other?

James: Yes, absolutely. That would be far more convincing, especially if they're in different cultures, that would be very much more convincing.

Nathan: On the other point, as well as to when they say the tensions in the narrative are evidence against copying, for example, because anyone who was copying could have gone. "I'm not going to introduce tension because that will make people further down the line think that, you know, like the stories don't cohere. But what if the later author, who had access to some earlier texts, actually disagreed theologically with something, is copying, but then decides, actually, I want to emphasize a different theological point. And so moves around the ordering of a story or maybe changes something. I mean, I think that stuff happens.And that introduces for us a tension story. And I don't think that that precludes copying. That would just be the motive that that would so they would have copied. The case that there's a tension doesn't rule out copying.

James: I wonder how it rules out embellishment. They say it rules out embellishment the fact that they include different details. But that's exactly what embellishment is, right? That's particularly bizarre.

James: And so I don't see why you would expect this at all if I imagine that you were interviewing witnesses to a crime or some other event like and they tell you accounts that are somewhat similar. But the people that are involved are different and only partially overlap, and they're coming at different times. And there's all these other details as the McGrews acknowledge here, they give some examples that don't seem to obviously make sense and seem quite different. You would think that, well, look, maybe something happened here, but that these people are not terribly reliable, they don't quite remember things properly or they weren't really paying attention. Something's going on there, right? You wouldn't just think, Wow, this is really, obviously good testimony because, yeah, because they contradict.

James: And the short ending of Mark has basically nothing in common with the other accounts, except for the fact that the tomb is empty, like the women see it and then they're scared, and they and they run away and don't tell anyone. That has nothing in common with the others which say that they told the disciples and the disciples came, at least one of them did, and then that Jesus appeared to the disciples. How can you say that those are just circumstantial variety? There's massive differences in the account.

James: And it's not like people deliberately make these things up. It's like "it must have been". This is this is what Modern-Day evangelicals do when they write their their harmonizations - "it must have been" then it turns into a new fact. So I think that that's probably like Well, "it must have been" that the women found it, but because no one would have taken them seriously, they didn't tell anyone -- because it accounts for why no one's heard of it before.

Kamil: This is actually very consistent with our background knowledge about how, like ancient historiographers put together their accounts because it's often the case, some historiographical accounts are actually just very plausible reconstructions of what must have happened.

Kamil: for example, imagine that the author of The Gospel of Luke, a belief that Jesus was raised from the dead, [...] And based on those beliefs he created a speculative version, what he perceived as as a plausible way the resurrection appearances would play out. And this is why we actually have the text and it is not because there were actually people in history who experienced Jesus. Plus, I think he was doing a lot of theological work as well. Like it specifically says that Jesus ate a piece of fish to rule out believing that he's a ghost or phantasma, I think it says in Greek, which is a counter apologetic against people who believe that Jesus didn't have a physical body when he was around on Earth. And I think the text being a product of this kind of historiographical practice is massively more inherently probable than Jesus actually being raised from the dead, actually appearing to people and actually eating fish.

Brian: Is it reasonable as a possibility that Mark, for instance, the women finding the tomb only because someone would make the argument that he wouldn't have put it in there unless it were true. And so this is a way of kind of making his stories sound more true, almost like I think the preface in Luke is kind of like that, where you insert something that makes it sound like it's legit. I think Lovecraft used to do that, throwing things in a fictional place (like a statement from a real journalist) to make it sound more legitimate.

Brian: Now, another another possibility, then, is if this argument has some weight that essentially having women testimony, it would be embarrassing and wouldn't be in it unless it were somehow legitimate, then you could think of almost textual or oral tradition evolution, where those stories that included that detail would be the ones that would get passed down. It's an evolutionary argument for why we we end up with a text that has it, because that's the story that would have been told again and again, and it had this extra little element of, "Oh, and it's got to be true because..."

Kamil: That's a really interesting hypothesis, one possible hypothesis would be that this is a double bluff. Right? The author realized that, "Oh, if I put this detail, it's going to make it look more historically reliable precisely because it's counter intuitive". But this is another alternative that it's a process of natural selection, which selects for stories that look authentic, even though historically, they are not.

James: Well, look, the reason like this is why it says this is because people hadn't heard about this before. So they all thought the gospels need to explain why no one's heard about it before, at least why it's not more widely known, perhaps. So they're saying, Well, look, it was women and no one believed them or that the disciples didn't initially believe them. So maybe they didn't know about it, something like that?

Kamil: Well, on my hypothesis, it actually becomes super, super easy to understand. By the time the gospel of Matthew is written, the author has not encountered the objection that the story is unreliable. By the time the gospel of Luke is written, this counter-apologetic is already the case. So there needs to be a counter-counter apologetic baked into the narrative to explain away or to invent additional data points to overcome the apologetic against the story.

James: One thing that the McGrews never do is ask the question, let's suppose the resurrection really did happen[...] four people who were there, or at least people who based their accounts on four people who were there, wrote down an account of Jesus life, what would we expect those accounts to look like? How does that then compare to what we actually have? It's obviously going to be speculative, but I think it captures rather poorly. You just look at the resurrection accounts as an example of that, that they're so different. And the McGrews try to explain this to explain this away by just, well, you know, they could choose to talk about whatever they want, right? They don't have to say everything. Just because they don't say it, doesn't mean that they're saying it didn't happen. But that just seems to me a really lazy argument. The fact is that you would expect, I think, to have a stronger concordance of what they actually do say and of what the events that actually happen. That itself wouldn't prove that they're historical because you still have issues of copying. But I don't think what you would expect to see is these sharp divergences between what you see in Mark and what you see in Matthew, say, and what you see in John, where they're so different. There's different theological overtones, there's different ordering of events, there's different things happening in different places. Is that really what you would expect to see? And I don't think it is.

Kamil: how how plausible it is that if it's the case that both the appearance in Galilee and the appearances around Jerusalem happened in history, how plausible it is that we would get one gospel mentioning only Galilee and the other gospel mentioning only Jerusalem. This is super easy to explain or my hypothesis, right? [...] It's not the issue of how much they explain, how much they narrate. It's the issue of there not being any overlap.

Actually, Timothy McGrew, when he gave a talk, he used a really interesting analogy to neutralize this kind of objection and it utilizes the fact that Lydia McGrew happens to be an orphan who was adopted to foster family. And he says, "Look, you could give two completely different accounts about Lydia, which both are going to be factually accurate. It's just they're going to be different because in one of them, you will be only talking about her original family and you will omit all the details about her being adopted, and the other account you will only talk about her adopted family, and you will omit the detail that she was adopted". And in that talk, he says, "when I present people with this they can't believe that it's actually describing the same person, even though it is." And I'm thinking, Yeah, my point, exactly. Why is it the case that people are surprised that it's not describing the same person? Well, because that's not how people narrate stories! The surprise of people, is evidence for that being really, really implausible. It's really implausible that you would narrate the two different accounts. Basically, they would only have appearances at one place, and the other appearances in a different place if both sets of appearances actually took place. This is the same with the birth narrative of Jesus. Right? But there is almost no overlap.

James: the accounts say that the women told them that Jesus had risen. Peter runs to the tomb and sees that it's empty and then Jesus appears to him. So I think you've got a case where the women tell the disciples, Hey, Jesus has risen, and then the disciples are now in a state of expectation and I presume excitement as well. I just think that this is not even consistent with the accounts, assuming all the details of the accounts are accurate, which I don't. But even if you just take it on face value, that isn't what the accounts say. There's no instance in where Jesus appears to all of the 11 prior to having appeared to at least one of the women or and or a single disciple beforehand. And that person, having told the rest of them, there's always an individual appearance, which is then reported to the group first, which is exactly consistent with my account, which says that there was a contamination effect, that an individual hallucination or some other experience which was reported to the group led to an expectation that prompted collective experiences.

Nathan: I think of that there's a Netflix documentary released recently on supernatural claims and there are a lot of people in that who had children who had died and they were grieving in those states. And then whenever a medium would tell them I've contacted and I'm talking to your child. Initially, the initial contact, someone would kind of be like, "Yeah, I'm skeptical. I'm skeptical. I have always thought of myself, you know, I'm an atheist, a freethinker, So I'm really skeptical of things like this." But then when they're told that, they sort of they dwell on it for like a week or so afterwards, and all of a sudden it becomes more plausible because of the hope that it kind of gives them that that child is somewhere that can be contacted and isn't isn't gone. And then they use that initial skepticism as evidence that they must be correct because, "I was such a skeptic, I would not have concluded that this is a case of truth."

James: So that point about the saying that they were skeptical. That's called avowal of prior skepticism. We've talked about this in my book before. I cite in my book how this is a known and is a discursive strategy that people use to try to highlight the paranormal activity taken seriously. Both in paranormal and religious experiences it's very common. It's interesting to me, having actually looked at some of this literature that so many of the things that are appealed to as sort of features are actually known in the broader literature as strategies or tendencies. So one is the avowal of prior skepticism. Another one is irrational belief persistence, concocting ever more elaborate explanations for why the belief should be held. Memory contagion would be another one that seems relevant here, trying to develop a just-so account as well. This is how it must have been kind of thing. So I think this article is similar to many others in that they just pretty much ignore most, if not all, of this sort of stuff.

Brian: I think earlier on in the text, we saw that they were just going to take all these statements as essentially given - everything in the text we can just take as true. Why would they consider these other things, when they're just going to take every single statement in the Gospels as true?

James: Imagine if Jesus said "blessed are those who proportioned their belief, according to the evidence?", of how different would things have been if he'd said something like that?

Nathan: how do we know that they were dying for that claim?

James: How could you establish someone who's willing to die for something -- that it's literally, specifically for that claim?

Nathan: think about the persecution of Muslims by China. It's not specifically, the Chinese government is like, "Oh, what's your theology? What are the propositions in your theology?" It's just that they belong to that group. I suppose we're talking about Jewish persecution and Roman persecution. The Jewish kind of persecution is just going to be anyone who deviates from the prevailing theology that the relevant power groups have. And then the Roman kind of persecution is kind of going to be similar, but it's just a different set of beliefs. And it doesn't it doesn't mean that it's specifically for because of the truth of this claim that Jesus had risen again, that that might be one of the claims that they believe it could just be for being associated with this group preaching.

James: the Romans wouldn't care less whether the Christians believe that Jesus or the dead, what they cared about was that they wouldn't sacrifice to the emperors and that they were spreading a religion that was therefore politically destabilizing. So if they recanted that, I mean, the Romans couldn't have cared less about that. [...] did anyone actually persecute them specifically because of the particular theological belief of the bodily resurrection? I'm not convinced that that was the case. What's the evidence of that?

James: The point is that to say that we know that 13 of them were willing to die for a specific claim. First of all, we don't even know much of anything about what happened to most of them. Second of all, we don't know that they were willing to die, because how do you establish that even if someone actually dies, you can't establish that they were willing to die because it might have happened just to try to avoid it? I don't know how you establish that, but let alone establish that they were willing to die specifically for that proposition, as opposed to a whole bunch of other things that they may be willing to die for, just as like the general belief that Jesus was the Messiah, for example. So apologists just push this so hard when there's actually so little evidence for it.

Kamil: The Jews were persecuting Christians on the basis of the Mosaic Law and the Mosaic Law. The prescription for blasphemy is death, and it doesn't matter if you're sorry.

Kamil: So apologists use this line of this detail in the Gospel to essentially establish that the disciples would not believe in Jesus's resurrection unless Jesus really appeared to them physically, unless they had visual, auditory and tactile experiences of his body because they were aware of things like ghosts which don't have physical bodies. The point is that on the background knowledge, ghosts don't have physical bodies, so they had to experience something that would rule out that explanation. That's the apologetic line of reasoning. Because if it was the case that they didn't experience Jesus having a physical body, they would just conclude that that was a ghost that wasn't actually bodily resurrection. But if you look at the relevant background knowledge, you find no shortage of ancient accounts where ghosts, phantasma, spirits, these kinds of entities actually do appear to have physical bodies. For example, they fight people, they have sex, and they eat. There was an apparation of Helen in some of the retellings of the Trojan War while the actual Helen was in Egypt the whole time. And the apparition tricked everyone into believing that Helen is in Troy for 10 years. While she ate, supposedly had sex with Paris and then the second husband. So this apologetic actually doesn't work about Jesus. Having a physical body would not convince people in the first century that he's not a ghost, because in the first century, we have ghost stories about ghosts having physical bodies. For [Luke], it's important for Jesus to have a physical body for theological reasons. Because then that means people are going to be given resurrection bodies after the general resurrection.

James: "inspiring, kindly and helpful" He's portrayed consistently by the same author. How could that have happened unless it was so?

Nathan: "a touch of amusement in his tone" I mean, again, it just seems exactly like narrative devices like when I was doing high school English.

James: We started talking about the appearances are reasons to think the source of the appearances date back to eyewitness testimony. That is, that they're genuine accounts of the disciples having related these experiences, not them having been developed later. So when that's your goal and the best thing you can come up with to say is, well, it's consistent with how Jesus is treated in the earlier part of the gospel that also narrates the appearances. It's the just-say-anything response. [...] I think what they're really saying is that it feels convincing to them, It feels genuine so therefore it is.

James: why is it that if something was if "the experience was based on some sort of spiritual rush of enthusiasm that led to a group experience of risen Jesus", blah blah blah that that would somehow preclude them claiming to have "extensive and direct personal communication with the risen Jesus"?

Kamil: this makes sense on the assumption that the content of the gospel is just written down what the disciples really sincerely believe they experienced. But of course, on our hypothesis, what the content of the post-resurrection narratives in the Gospels has almost nothing or very little to do what actually, the followers of Jesus experience shortly after he was crucified and died - those are two completely different stories. And the reason why the text is that way has nothing to do, almost nothing to do with what was actually going on.

Nathan: Sorry, I was just an irrelevant conversation about why would you wear a mask when you're vaccinated Having these kind of conversations about religion always brings out people with like crap epistemology about other beliefs as well. Oh, you're skeptical about the vaccine? And you also have a bad epistemology when it comes to assessing resurrection evidence -- I could have never have guessed.

James: Well, this is the dangers of propagating bad epistemology. I've said that it leaks over into other areas, and I've been talking about this for years, and I think that the coronavirus has given us a really good example of that. How crappy ways of thinking about some things can lead you down to really harmful results.

Kamil: there is this counter-apologetic, which I think it was worth mentioning. If you assume that in the Book of Acts is literally what happened to history, then why is it the case that there wasn't any manhunt for? There wasn't any question about what actually happens to the body, right? Because is there was a body missing, which would mean for non-Christians at the time that either Jesus wasn't really crucified, which means he's an escaped convict or that he actually died and someone stole the body, which was a criminal offense under both the Jewish and the Roman law. So why is it the case that there wasn't any investigation done about what actually happened to him? I'd like, I think, if something like that happened in history, and if it's the case that Peter was, for example, arrested as a known associate with of Jesus, I think he would be investigated as a suspect in body death. Right? But that's not what's depicted in the book of Acts. It's actually interesting if you read the book of Acts, it almost proceeds as if the empty tomb didn't exist.

James: So we know that Paul converted, but we don't really know much more than that. And the account that's given in Acts doesn't really find much corroboration in Paul's actual letters, which itself is odd. Like, you would've thought he would talk about that more. I suppose you could say, Well, that's an argument from silence, but they use that when it suits them.

Nathan: "we shall place no weight on the experience of the companions" Wouldn't discrepancies be evident, like shouldn't we take that into account when we're trying to assess the evidence for it?

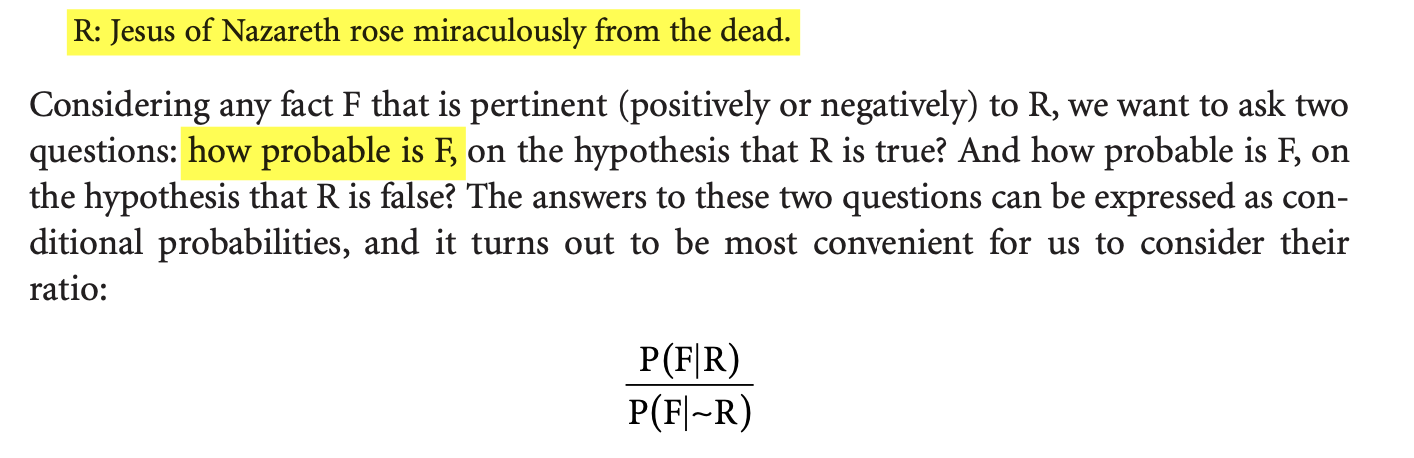

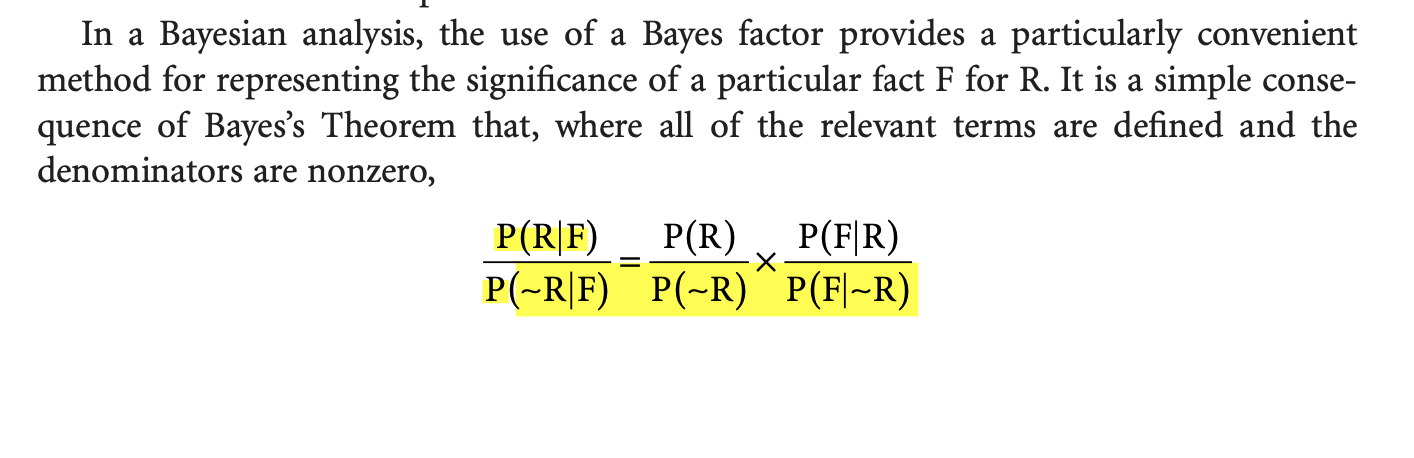

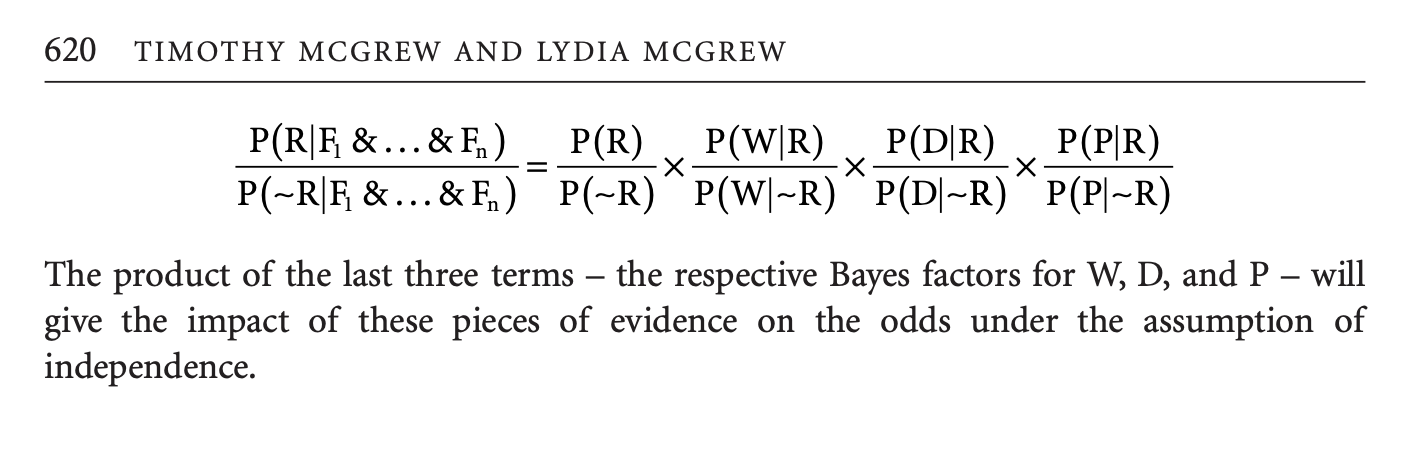

Brian: So we have the posterior ratio there on the left, the probability the resurrection given all the facts compared to probability of not resurrection, given all the facts. And then we have the prior ratio, which they ignore. They carry it around for a little while, then they get to drop it and then we have the likelihood ratio. So the likelihood is generally like assuming your model is true. What was the probability of the various facts? And that's that that term is what we call the likelihood. It's that first thing they're writing down is a likelihood ratio. And if you're ignoring or if you basically say that priors are equal. That's another way to do it. If the priors are equal then the posterior ratio is the same as a likelihood ratio, but they're just essentially ignoring the priors.

Brian: Most of those techniques, things like the AIC and the BIC, are approximations of the full analysis where you have a model that has some flexibility to it, so you have models that have a range of parameters, and what you do is sum over all of the different parameters weighted by the prior probabilities of those of those parameter values. And what you get kind of automatically is a penalty for more parameters that doesn't increase your fit and they're sometimes called the Occam factors. And it's also why they talk about simplicity in a model. And simplicity doesn't have to do with the number of parameters or the number of components, it has to do with how flexible your model is and what kind of range of values that it can have. So this is one of the things I comment on in my writings is that theists will often talk about the concept of God being simple because they only have very few components -- just one word. But complexity has to do with flexibility. Because God can do anything at all that it's infinitely flexible and would receive essentially an infinite penalty -- probability would be near zero.

James: All they're doing is multiplying a few numbers together, which they just sort of say, we're just going to assume they're independent because they don't really have any other way of dealing with it. So although they talk about Bayes as a methodology, they're not really using any of those tools that Brian was just talking about, which is one of the reasons why I've said before that they could just jettison these equations they wouldn't really lose anything. It's dressing things up in the trappings of a probabilistic theory that gives it the veneer of scholarship that it doesn't genuinely have.

Brian: I think there's that there's almost a psychological value in making things complex enough that no one's going to check your work and they'll just take your word for it because it's too detailed.

James: This summarizes the key terms here. So are there is a resurrection hypothesis. So those are actually our priors, which remember they're kind of not actually interested in. But then we've got \(W\) given \(R\) over \(W\) given not \(R\). So that's the women's testimony, right in the empty tomb. As Brian said, they sort of stick around for a bit and then kind of disappear and. But I mean, they're writing the full posteriors here. It's unclear why, because they're not actually addressing that. Well, the second three terms are different parts of the likelihood. So they've been split up because they're assumed to be independent of each other, which as I'll comment on, this doesn't make that doesn't make any sense, but just to explain the terms. So again, it's the women, the disciples and then Paul. They are claiming here that they are all independent of each other, conditioning on the resurrection. So that amounts to the claim that given the women found the tomb empty and reported it, it is no more or less likely that the disciples would see Jesus, that they are independent of each other, right? Does that seem reasonable to anyone else because that seems completely ridiculous to me.

James: How does it follow from the resurrection that women would find the empty tomb? How does it follow that there would be an empty tomb, I'm not even sure that that follows from there being a resurrection. Could there be a resurrection and the tomb be lost or the tomb be taken up into heaven? Or even there could still be a body in the tomb, or just appears to be a body, I don't know, it's God, can't he do that if he wanted to? Already, I don't agree. Or they just find Jesus alive in the tomb. Yeah, that that's another possibility.

James: I thought we were not looking at prior probabilities, but now we are. This is what I mean. They do this repeatedly. I could say we can set aside the possibility of a resurrection because that has prohibitively low prior probability, but I guess that's question begging, and they're just looking at the likelihoods. But then they say exactly the same thing against the skeptic. It's unbelievable.

James: So we just get a whole bunch of assertions that the probability is low, like this is what I mean, this is consistently what these sections are about. It's them saying that it's implausible without actually giving really good or in some cases, any reason for actually thinking that it's not a good explanation.

James: "is very difficult to see why Joseph of Arimathea would care enough about what happened to Jesus' body to provide his own new tomb for it immediately after Jesus' death, but then would want to move it out as quickly as possible after the Sabbath" Interestingly, then, at the end, here we get precisely an explanation for that. So the hypothesis that I was novel to me that I discuss is that Joseph was prevailed upon by perhaps the Jewish authorities, or perhaps even the Romans who knows exactly, to temporarily store the body in his tomb because it was close by and it needed to be taken down on the Sabbath evening. That was part of Jewish law, and also because the Romans really didn't want Jesus's body to be disposed of in a public place where that there could be continual disorder. They wanted it to be put somewhere that was quiet and out of the way and private until things died down and then after the Sabbath, they could be moved. And I don't really think we get much here about why that is so implausible here. We're told it is implausible multiple times.

Kamil: And Bart Ehrman says, OK, I don't know. I'm just going to make up something out of the blue. He didn't do any preparation. He just said, OK, let's assume that the relatives of Joseph of Arimathea who were not followers of Jesus actually found out that he was buried in the family tomb. They were really outraged. They didn't tell anyone that they have a problem with it. So they just decided to go to the tomb at night, take the body and bury it somewhere else. They were stopped by the Roman guards. They were all killed for body theft. And the three bodies were like, disposed of. They were just thrown in a ditch. Nobody ever finds out. So this explains why the information wasn't then disseminated because everyone involved was killed. And the Roman guards didn't have any reason to tell anyone about it. Or even if, like days later, they heard about someone making it a Resurrection claim, they would have no reason to tie that experience with that specific claim. And he says, Do I think this really happened? No. Is it very probable? No. But it's more probable than resurrection.

Nathan: Am I just meant to sort of consult my intuitions about them?

James: Well, no, because your intuitions could be quite different to theirs, they are just saying that that is their estimate? Right? There's no model here. You can't really interrogate anything. All you can say is given what they have said, do you agree with their assessment of 1 out of 100 roughly? And if you don't, well, then they say, well, there's nothing that they can say, or they can just say as they deplore your judgment.

Kamil: This is exactly one of the issues with, for example, Richard Carrier. He gives the reasons for why he thinks that the the expected us of the evidence goes in either direction, for example, that this piece of evidence is what expected on historicity versus mysticism. I cannot give this like a lower or higher estimate, than, let's say one in two in favor of historicity. And the and then repeatedly throughout the book, he says, Well, if you have a different estimate, then feel free to publish your own like a work showing why the estimate should be different. But the obvious issue is that the reasons why he gave gives at most point to in which direction the ratio should go, whether it should favor one hypothesis or the other. But there is no connection between the arguments and the evidence that he presents and the actual numerical value that he then gives. So one in three is just as arbitrary as one in five or one in 10.

Brian: You would think that in some cases, you might be able to have some kind of reasonable bounds. If you're talking about a rare event of some kind then you know an upper bound of like one third might not be outrageous -- it has to be less than half because we know that the event is somewhat rare, then conservatively you could do one third. And then there's going to be of a lower bound in terms of your ability to even estimate. And so you could follow through Bayes theorem with ranges to posterior ranges as well. They won't be very particularly narrow, but I could see one being able to do that.

James: So the fundamental problem here, as I mentioned before from my point of view, is that they are using the idea of Bayesianism in terms of subjective degrees of probabilities, multiplying probabilities together and so forth. But then that's all they've done. So in doing that, they can describe their own degrees of belief. And in that sense, it's completely fine for them to just pull numbers out of wherever because they just describing what they believe, right? And they can multiply those numbers together and get results as long as they're consistent with the probability axioms, that's fine. The question is whether they should have argumentative purchase on someone who doesn't already agree with them. What reasons should I have for accepting their analysis? And in my view, the only way that that's going to work is if they either provide base rates or they do some sort of actual modeling of some process, psychological or sociological, whatever and are able to use that to derive some estimate of some value, which they plug in to the model at some point.

Nathan: And this is why I think it's important not to ignore the base rates when it comes to doing something like this, because the base rate is tethered to reality in a particular kind of way where I can't imagine my way out of it. Whereas it seems that this is entirely predicated on like how plausible, like how a story sort of makes me feel, like how it sits with my intuitions and by how imaginative I am.

James: this is just to set this up. So one possible explanation that's in the \(\sim R\) space is that it was they lied about it. They made it up. So that's what they're responding to here.

Nathan: it's like it's always if they're in a position to know that they were wrong, right? But it's like if they're in a position to know where they could have known they were wrong, then they would have known if they were wrong. But I just don't think that's right. The Muslims who flew into the twin towers, they're in a position in the 1990s to have access to enough information to know that the Koran, you know, like Koranic studies and like the metaphysics and all the problems if they're in a position to know that it's that Islam is false. Yet they still flew planes into the buildings.

James: So then they talk about the possibility of some of the disciples stole the body, which I actually think is a possibility. They're not maybe that the disciples, but just some of the followers of Jesus stole the body for something similar to what Kamil said, but maybe for slightly different reasons. I don't see what's so implausible about that, but again, they kind of don't like that, but I don't think we can belabor that point there.

James: Now again, they don't explain why this is so bizarre. Is it more bizarre that someone had a twin brother who pretended to be them deliberately or maybe even kind of accidentally, or a man came back from the dead? Which is more bizarre? So they're also talking about priors there. Again, they keep going back to priors whenever it's convenient for the McGrews. What they're supposed to be addressing is the Bayes factor, which is the ratio of likelihoods, which has nothing to do with how plausible an explanation is. That's the prior. They can't seem to keep that straight in this analysis here. And also, they don't even do a good job explaining why things like that are implausible. They just say it's bizarre, so barely worth mentioning. Why is it bizarre? I mean, maybe it's a little unusual, but then isn't a resurrection bizarre in that sense as well? Why is that more bizarre than a resurrection?

Brian: So it really is amazing that every single one of their critiques of ideas that they disagree with, they argue against the prior and they don't talk about how well that particular explanation, regardless of how likely it is or how likely prior to the data, but how well it explains the observation. They just say, Oh yeah, this is just implausible. Every single one. And why is it OK for them to do that and it's not okay for the skeptic to do that?

Kamil: It would be really interesting to ask them how to explain Jesus appearing in Christian literature, which they don't take as historically reliable. For example, the Gospel of Peter. How would you explain it, like how is it the case that there is a gospel which explains the appearances of Jesus, which didn't actually take place in history?

Brian: The probability of a singing cross is high on the resurrection hypothesis and lower than not resurrection hypothesis.

James: I will never understand how an apologist can, on the one hand, say if God can create the universe and fine tune the constants, then a resurrection is child's play, which I've heard them say. And on the other hand, laugh and scoff with the audience at the idea of a singing cross. Why is that implausible if God wanted to do that?

Kamil: All you need is a sincerely held but mistaken belief.

James: Apparently that's not enough because that's what they're arguing here. So they compare it to the idea of religious zealots. Now, I'm not sure why the disciples don't count as religious zealots. By most standards, I think that they would count as religious zealots. Obviously, they're not going to like that language, right? But again, this is just loaded language that they don't define what what the criteria are.

James: But anyway, they talk about a gambler in a fit of frenzy may offer 100 to 1 odds that the roulette wheel will come up red, but the gambler is apt to sober up quickly and abandon his enthusiasm if his child's life is put on the line. What evidence is there for this? Like people never lose their house because of gambling? That just doesn't happen according to them. Nathan: Oh, don't fly planes into the twin towers. James: It's just unbelievable. Like, where did they get this stuff from?

James: let's take it seriously. Their claim is that people in a state of religious frenzy or similar to that, whose judgment is clouded, sober up and think more carefully and critically when the stakes are high on the line and therefore unlikely to make those sort of mistakes. What is the evidence for that claim?

Nathan: Well, I think the evidence is is exactly the opposite. When these stakes become so high, there's like a sunk cost fallacy involved in it.

Kamil: I think the underlying assumption here, which I think is false, is that if someone believes something very strongly, it must be because they have very good reasons for it. And if they didn't have very good reasons for it that they wouldn't believe it, that strongly. But I think if anything in our background knowledge, it's the knowledge that this is not how people work.

James: Yes, and the McGrews kind of anticipate this objection because they say in the next paragraph, it is sometimes urged that kamikaze pilot suicide bombers and Nazis are willing to give up their lives for what they believe to be true. So that's a sort of a subset of what we were talking about. What is their response to that? The answer is that this description blurs the distinction between the willingness to die for an ideology and the willingness to die in attestation of for a fact.

Nathan: that's just begging the question!

James: But what they believed was a fact, I suppose. But what is an ideology other than facts that you believe, right?

Nathan: Yeah, they're assuming that the conclusion that they want falls under the realm of facts, which is the very thing that the Bayesian analysis is supposed to be establishing, right? We haven't actually established that it is a fact. You can't appeal to that.

James: What do you think that if you ask the disciples, are you willing to die or are you facing persecution because of your belief that Jesus died and died for your sins and all that, or because of the empirical fact that you believe you witnessed Jesus rise? Do you think that they would even understand the distinction you were trying to make with this?

James: The Nazi examples [...] so many people attested to the charisma of Hitler and his success empirically like, look at all what he did for Germany in recovering territories and building up the country -- those were empirical facts to them that they attested to, that supported their worldview of that Hitler, which they actually believed, was sort of ordained by Providence. The point there is, I think that there absolutely are empirical facts that they would have pointed to in defense of or in justification of their views. And likewise, the disciples, I think, would have had empirical facts that I would have wanted to, but also that fits in a big ideology. What the McGrews are going to do is just artificially distinguish, separate those things and say that it's if you're willing to die for an ideology that doesn't really count for anything. That doesn't mean you're likely to rationally critique it. But if you're willing to die for any empirical fact, then you're going to rationally critique it and you're going to end it. You must have good reasons. There is no justification for that distinction. It's not clear that the distinction makes any sense at all. And it's not clear that it separates the cases that they want to, because I think that it would be both of it would be ideology and empirical facts. In all of the cases, they're just making things up. They're just making things up that sound the slightest bit plausible.