Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In this YouTube episode, Bad Apologetics Ep 18 - Bayes Machine goes BRRRRRRRRR I join Nathan Ormond, Kamil Gregor, and James Fodor to discuss Timothy and Lydia McGrew's article in The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology entitled "Chapter 11 - The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth".

It's 9 hours long, but I am only on for the first 7 hours. This isn't a complete log of everything said, but I tried to include the main points. I also started with a transcript, and edited it for clarity (e.g. removing ums, and repetition) but there may still be some weird typos from the computer generated transcript that I didn't catch. I will try to quote Nathan, James, Kamil and myself if it comes from the episode. All other text is mine, commentary either at the time or sometime afterward.

The parts of this document are here:

And the link for the full video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/yeCBpO7pSRM

The main issues are:

Nathan: "So then so what would induce grown men to break with the religion, men to break with the religious community in which they had been raised and to confess with their blood that they had seen with their own eyes and handled with their own hands their dead rabbi raised again to life." Well, that second part of the sentence is contentious, isn't it? Because it's not clear that they're dying for that? It's they had a belief. Right? So the question should be what would cause grown men to form a belief that they had seen the resurrected Jesus physically? Right. And then break with that religious community and stuff. And then that's obvious: cognitive biases, distortions, grief from their death, cognitive dissonance theory, sunk-cost fallacy, etc....

James: Swinburne does this as well. They want to hermetically seal-in people in the belief systems that they grow up in or were raised in. And by this logic, you should never see religious innovation because like, well, people are trapped in their religious community. They can't take ideas, like, where does the resurrection idea come from? (Nathan: Except when the true) but then where does Islam come from? What is Mormonism come from? What does Buddhism come from? Where do all of the other messiah claim it's come from? The work of the devil? Clearly.

Kamil: Well, in this entire section, this question and the follow up is just lack of imagination. This idea that the disciples broke away from the religious tradition. I'm not sure they would frame it that way, because it's always the case that when you have theological innovation it's only a theological innovation to outsiders, but people in the group actually think that, no, they are rediscovering the true origins of the faith that was polluted by the outsiders.

Nathan: Well, I just thought of something that actually, I think even more would support the non-resurrection hypothesis. And that's in the cognitive dissonance theory there's also that how difficult it is to join a group actually makes you more likely to stay and not pay attention to disconfirming evidence. So like fraternities, you have a horrible induction process and stuff like that. Well, people are more likely to report that they have positive experiences when there's a difficult joining process than when there isn't because they're looking for ways to kind of justify why they did like a bunch of dumb stuff. Let's think about the case of Christianity here. Say you want to join our group. You're going to have to break with the Judaism of the group that you're in and be persecuted by all these people. And then you join. Well, what are you going to do? Are you going to go, "Yeah, actually, I was wrong" or are you going to look for rationalizations to not have to to justify your actions that you took in the first place? So I think, again, like a best kind of psychological theories about biases and things, there's even more reasons to confirm the non-resurrection theory.

James: So they mentioned his disciples weren't anticipating any miracle, let alone a resurrection. I don't know how they know that. It's interesting that their own scriptures say that they should have been because Jesus said he was going to be resurrected. So I guess we're just completely ignoring that. The appearances to the disciples always is preceded by the women telling them -- there's always some expectation that precedes the appearance, even if we take the details at face value, which I don't think we should.

James: Now, the next sentence is very interesting. "Messianic expectations in Judaism at the time did not include the resurrection of the Messiah, except in the general resurrection at the final judgment". Is this a reason for thinking that the probability of the resurrection given Judaism is actually low because it seems to be right, but somehow it's only in evidence against the ones that they don't like, but not against their own hypothesis.

James: "The disciples sometimes fail to recognize Jesus."" Now that is advanced as a reason to be skeptical that they were expecting to see Jesus, right? First of all I don't know why we should trust that as a detail. But also, the non-recognition motif is super weird. How is that expected under the resurrection hypothesis? Why would you expect Jesus to appear to some of his disciples and then not recognize him? So I don't understand how the resurrection explains this. To me, it's bizarre under any any view, certainly on the resurrection view. There's no explanation for it. They just pretend that there is.

James: So they're saying hallucination theory has to be invoked for multiple people. And the plausibility, as they say, inversely related to the amount of detail that involves. So what they're saying is that hallucinations become less plausible as an explanation for a report the more detail that a report has in it. I would like to see a citation where they show why they are claiming that because I don't know of any evidence that claims that the more detail you give the less likely it is to be a hallucination. They seem to be just making things up.

James: In the footnotes here, they say in 27 here, they actually use a quote that I quote in my book talks about how comparatively dissimilar hallucinatory experiences of different people attain a spurious similarity by process of harmonization. And the quote goes on sort of explain some of the basic processes that operate to sort of harmonize accounts of individuals into a group account, which is what I think happened. Now what do they say in response to this? I'm glad they caught this, but what's their response? Their response consists of one sentence "But detailed experiences full of verbal and tactile interactions, both with the one seen and with other witnesses cannot be brushed aside like this." OK, so that's their rebuttal. They just basically say, "No."

Kamil: As far as I understand, under the hallucination hypothesis, the content of the experience is not actually what's described in the Gospels. When people say "maybe some Jesus's followers hallucinated". They are not saying, "I think there were groups of people that if we could interview, they would say, Oh yeah, I totally like poked through Jesus's holes" No, they are still saying that the accounts of Jesus's resurrection appearances in the Gospels and Acts are a literary creation, but they would say that the reason why they are there fundamentally goes back to some people having some kind of hallucinatory experience of Jesus and that grew over time. It got exaggerated, distorted and eventually this is what you end up with in the Gospels. So that's not even dealing with the actual hallucination hypothesis.

James: Yes, exactly. And apologists consistently make this, what I regard as a clear mistake. They think that hallucination explanation, plus memory, contagion and whatever else, has to explain the accounts as they appear in the Gospels, which it absolutely does not have to do, because that is assuming that the skeptic just takes for granted at face value, everything that it says in the Gospels. Whereas no, that's not what the skeptic, that's not what those 75 percent or whatever percentage of scholars who think that, you know, the disciples believed that they saw Jesus. That's not what most of them are saying. They say there was some sort of experience that the disciples had, which they interpreted as Jesus appearing to them. Not necessarily the same as anything that we see in the Gospels other than in the very broadest outlines of, you know, they saw Jesus. They thought they saw Jesus. But repeatedly, the evangelical apologists keep saying, Oh no, they can't explain all the details. We see that on the next page, where they start saying, I know, but like they gave food to him and they cooked fish. Like, how could they have? How could they have hallucinated that?

James: They say "then abruptly, they stopped". That is the resurrection appearance is stopped as Christ was no longer appeared on Earth and subsequent appearances were sort of different in character. Now my question is, first of all, why is it expected under the resurrection hypothesis that the appearances would stop? Jesus has been raised to life. He's back. He could be around for years, decades. I mean, forever if God wanted to be around forever, right? Like, why is it expected that they would stop after how many days it was? Actually, I think it's very expected that we would see this under a naturalistic hypothesis because and I can't remember if I actually talk about this in my book or just on my blog somewhere. But new religious movements that involve prophecy and revelation almost always fairly soon restrict the prophecy and revelation to particular people and particular time span. And the reason for that is because otherwise you can't keep control of the development of doctrine and who has power and prestige in the movement. There are case studies that have been done of this. There's almost always restrictions placed on what counts as a genuine revelation, either based on the person or at the time or something like that. So this is exactly, I think, what you would expect for a newly developing religious movement that entirely has nothing to do with God is that you would have some sort of cutoff point or criteria of what counts as a resurrection appearance. And this apparently Pentecost, was what developed in the early church, whereas it's not clear why you would expect anything like that if God actually rises from the dead. So again, they don't even seem to think about why something would be explained by their preferred resurrection hypothesis. It's just assumed that everything is explained. And then they ask, How do you explain this?

James: How do you know that Zeus would have no motive? Yeah, so poor old Zeus, he's just sort of left out in the cold there. I don't know why he's ignored so readily.

James: So they seem to be saying here that God wouldn't have provided an objective vision because that would confuse the disciples in thinking that he had resurrected. Which would be like deceiving of God? I really don't even know that the early disciples would have had the ontological, would have drawn the ontological distinctions that we are making here between an objective vision and a bodily resurrection. Maybe they would have, I don't know.

Kamil: That goes back to what I'm saying. So if you look at the development of early Christian literature, then all the way up until the gospel of Luke, these appearances are actually like true visions, right? They are not appearances of a body that's walking around, talking to people. At least that hypothesis is consistent with the account. And this distinction between a supernatural veridical vision and an actual body being there that you can touch in the room is first introduced in the gospel of Luke. I want to emphasize again that in the gospel of Luke in that post resurrection account, it specifically says in Luke that Jesus ate a piece of fish so that the disciples wouldn't think that he's a ghost. Right? Yeah, I think that's protesting too much. I think that's a counter apologetic. That's why the author takes care to mention that.

James: And my point was that under an assumption of a true resurrection and divine inspiration of the Gospels, would we expect to see these sort of developments comparing Mark and John being sort of the most obvious and the theological flourishes that you see in Matthew and in Luke about all sorts of different points -- guards at the tomb and the people walking around Jerusalem and the mention that they touch Jesus, that Jesus ate fish so that they would know he's not a ghost. These things seem much more plausible under the idea that these are particular debates and theological concerns that the authors had at their time that didn't exist in in the time of the previous gospel authors and that they wanted to put in otherwise. Like, why wouldn't you just start off with the higC christology that you have in John and all of the relevant details and heck put in the Nicene Creed in there, just just so that God can have his bases covered and make sure that no one misunderstands -- this goes a bit beyond, I guess, the point being made here, but I just don't think we would expect to see texts like this under the assumption that Jesus was raised from the dead.

James: I would like some citations about this and what sort of mental illnesses are necessary for these sort of delivery effects, because as this is, I think, incorrect hallucinations actually quite common. And I don't know that there's any evidence that they can't be integrated into other experiences. They're not necessarily associated with mental illness, either. They're quite common in the healthy population, so they're just making things up at this point. This is apologetics through making things up. There's no citations or explanation of that there at all. And they also don't know that the conditions, like the conditions that they are referring to, are absent. How do you know that those weren't present? Yet again, just making it up?

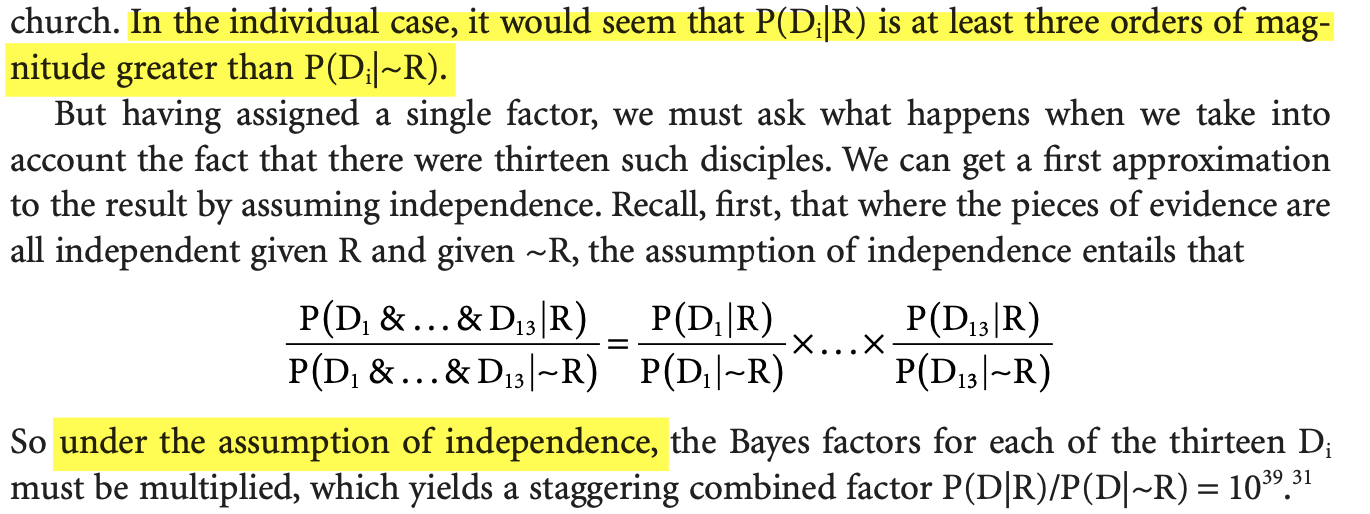

James: They say the probability of a single disciple reporting experiencing Jesus under the resurrection relative to not-resurrection is one in a thousand. So three orders of magnitude.

Nathan: Where does this number come from? What if I just go, Yeah, but it just seems to be different like -- what can we appeal to?

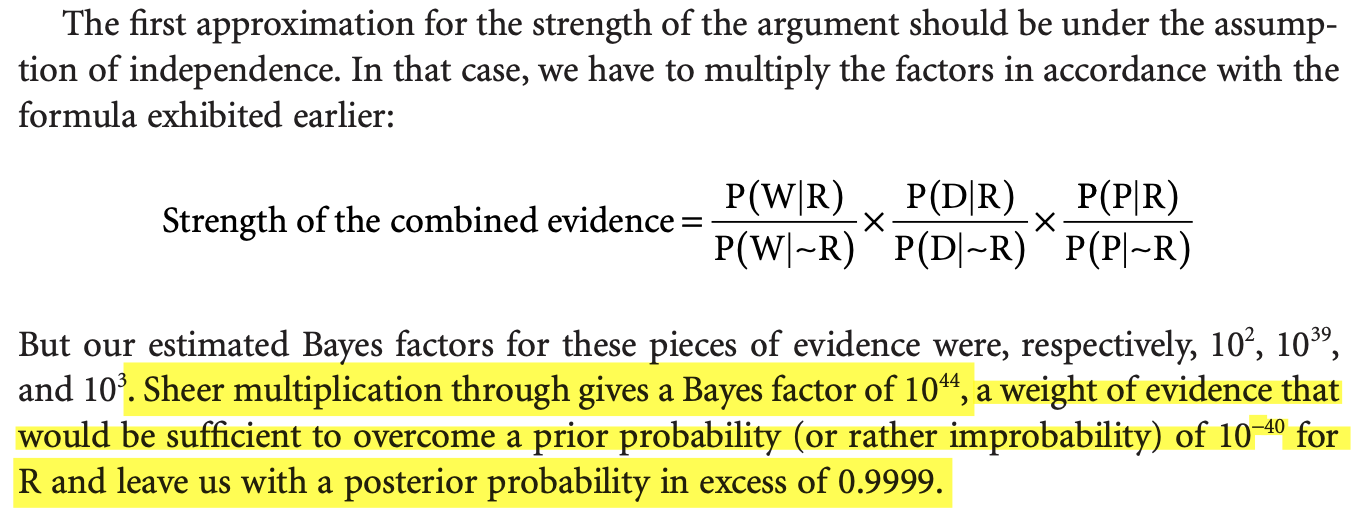

James: They can deplore your reasoning, but they can't say you're wrong. So the point is that they're taking a thousand is the Bayes factor for a single disciple. And they're saying that there are 13 of them who saw Jesus. So if you multiply 10 to the three by itself, 13 times you get 10 to the thirty nine, which is that that number there. So they're building up to the 44, that is. We get we get 10 to the two I think from the women, ten to the thirty nine from the disciples and I guess the rest comes from Paul. So there's a whole separate subsection the independence. So we'll discuss that when they discuss it.

James: But the question we're trying to address here is what the Bayes factor is. How expected is Paul's conversion under the resurrection, given how expected is it or how likely is it under not-resurrection? Now, I don't know that anyone has a very good explanation for Paul's conversion. The question is though, how probable is it under the resurrection? Why would you expect Paul to be converted given the resurrection? What is the connection there at all? They don't even discuss this. They don't mention it.

James: "On the assumption of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>R</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">R</annotation></semantics></math>, there is no difficulty whatsoever accounting for <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mi>P</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">P</annotation></semantics></math>", which is Paul's conversion. But what does the resurrection have to do at all with Paul's conversion? God could appear to Paul if he wanted to irrespective of whether he was resurrected. Nor do we have any reason to think that God would have any business appearing to Paul. Why would he want to do that instead of appearing to anyone else or groups of people or no one at all? There's no explanatory value here at all. They have nothing to say.

Nathan: You know, sometimes I'm thinking when we say they've literally pulled the numbers out their ass, that that sounds a bit harsh, but where has this number come from other than that? what belief do I hope with like 10 to the minus four?

Kamil: You know, like let's say that there is some mundane claim from ancient history that we have a very well evidenced even maybe even better than what we have for the New Testament, right? Let's just say that it's a mundane claim that Cicero makes it one of his letters where he literally wrote the letter like moments after it happened. And that same claim is also understood by a bunch of historians who covered at the same time period somewhat later. Like, would they also say that the likelihood ratio is this astronomical in favor of that event actually happening? It's way too high. Contemporary historians of antiquity are not this confident even about very mundane claims in the historical record, because they realize that even if it's super mundane, even if it's relatively well evidenced, they realize that all kinds of things going on that are separating us from the actual historical events 2000 years ago so that we don't have any information on things like distortions of information in transmission and stuff like that that it's just not appropriate to be super confident, especially especially not astronomically confident, like this is the level of confidence, which I think is not even warranted when it comes to the findings of in like experimental science, like experimental physics. Because even in experimental physics, there are all kinds of things that could still go wrong with the equipment that the machinery and stuff like that, right? And even if you have multiple people, it like different labs around the world confirming the same event, it could still be false positives, right? So that's I think that's a very powerful reductio, at least against what they are doing in the paper with these specific numbers.

James: Take something that's sort of overwhelmingly, I don't know like that two jet aircraft flew into the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. That event, right? What Bayes factor would they give for that happening? I mean, it's hard to know what it could be, because the evidence we have for that is so much greater than the evidence of the resurrection. The number that would have to give is just completely obscene, right? And if you think about claims even from empirical sciences, Kamil says, I wouldn't I don't think I'd give 10 to the 44 of anything, right? That is just so ridiculously high. Remember, 10 to the 12 is a trillion. So like one in a trillion against you could think of it as. And that is a very, very high confidence. It's hard to emphasize how high 10 to the 44 is as an odds ratio. And the fact that they are giving that to an inference event that no one, there's not even testimony of anyone seeing this, it's an inference that would give to explain a bunch of facts which are tendentious. To think that you can get even close to 10 to the 44 is just ludicrous.

James: So they're saying that the probability of the evidence is that we mentioned, occurring under not resurrection is equivalent, relatively speaking, to someone winning $100 million ticket lottery more than five times separately, independently of each other. That's the level of unlikelihood they're claiming we as the not-resurrection people have to swallow.

Nathan: I don't even know that I would be that uncharitable to the resurrection side of it.

James: I mean, I would give a higher probability of young-earth creationism being true. 10 to the minus forty four, for goodness sake, that is so ridiculously low.

Because they don't make any attempt to compare to other models, other situations, they uncritically accept a Bayes factor of <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mn>1</mn><msup><mn>0</mn><mn>44</mn></msup></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">10^{44}</annotation></semantics></math>. It really is absurd -- nothing, even in the physical sciences, rises to this level of confidence and they don't seem to bat an eye.

Part of this I think is a defense mechanism, so they don't have to deal with the super-low priors for the resurrection -- if the likelihood ratio is off the charts, then it will overwhelm nearly all priors. Lydia McGrew makes this case in a video response about setting aside priors.

Nathan: here's why the methodology they've used is crap and shouldn't be used by people when they say how the compounding of independent pieces of positive evidence can rapidly create a powerful cumulative case, even for highly controversial claim. So think about the gremlins in my closet. So what's the case? There's noises coming from my attic. Given that there are gremlins in my closet. And now take what would be some other piece of evidence as well. There's also a leak coming from the attic. And these gremlins are like urinating and stuff up there, which is causing a leak, obviously. So that's also really expected. And so and then let's say there's four or five different leaks in the attic. So let's just multiply each of those together because they're each independent lines of evidence, right? And just keep. And this is how the Bayes Machine goes Brrrrr. And that I think just is demonstrative of this being a really bad way of trying to use Bayes Theorem to compare true beliefs about about something.

The method Nathan outlines here is structurally the same as the McGrews. You ignore priors, have lines of evidence which you claim to be independent and support your supernatural claim, multiply all of them together to get a really huge Bayes factor. It's completely naive.

In addition to all of the other failures, they also don't recognize that this naive accumulation of evidence doesn't actually work in multiple-model comparison, where you can get non-monotonic effects. This occurs in some very simple cases and is easy to see, but they never seem to address them because they fail to have any serious model of how their data is produced. There are other subtle effects even beyond that that can make more testimony even worse, when you include the process of taking seriously how we update our knowledge.

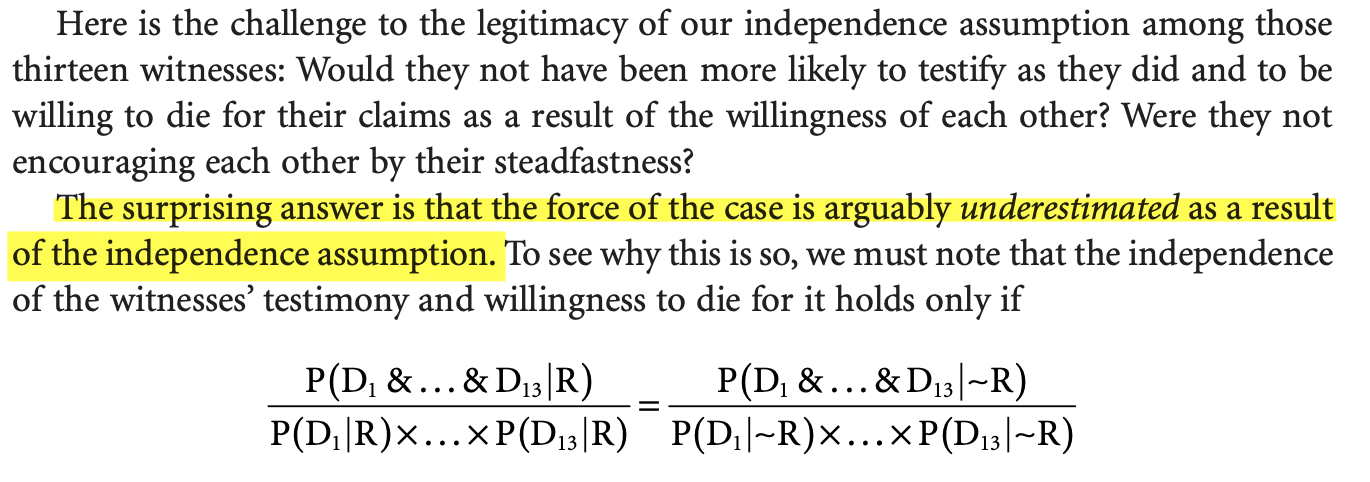

James: They don't actually say that they're necessarily independent, as they say here. In the quote that I've highlighted here, the force of the case is actually underestimated as a result of the independence assumption, so they are dependent. But in a way that actually increases the odds ratio, so they're actually being conservative in assuming independence. Now that is an interesting one to get your head around. Let's think about what that means. What they are saying is that. Suppose you came to believe that one disciple, let's say, Peter, had an experience of Jesus and reported seeing him and so forth and being willing to die for him. They are actually claiming that it is less likely that another disciple say John would also have reported an experience of Jesus and be willing to die for him. They are telling us based on this statement here that I've highlighted that. Believing that one disciple came to experience Jesus makes it less likely than another one did. That is the content of this claim here now. Riddle me how plausible you think that is because that is such a ridiculous claim. It is so stupid. I can't believe that they would actually say this.

Here, I think that they are leaning on the willingness to die causing a reduction in the reporting of the second disciple.

James: So they're saying that basically, once one disciple heard about, you know, say, Peter being martyred, that a second disciple would become less likely to stand firm in their testimony.

Kamil: that depends on what's the background knowledge on martyrdom and how it was perceived. Because it's clear from early Christian literature that Christians actually didn't perceive martyrdom as something negative or something that they should avoid. They actually, like looked forward to it. They didn't mind this. This is something that you find consistently in the early Christian literature, Christians were actually happy about being persecuted. [...] And I think that makes sense because they believe that if you are martyred that means that your salvation is secure. [...] They would basically commit suicide by cop by handing themselves in massive numbers in some cases. There are reports of entire crowds of Christians walking up to the Roman procurator and demanding to be martyred for the Christian faith.

James: This is such a silly argument, it feels like that they knew that they had to address the independents. The McGrews had to address the independents issue. And so they adopted the "just say anything" approach where their arguments are so ridiculous that I don't understand how any thoughtful person could even entertain them. So as as Kamil said, we have ample evidence that many other Christians sought martyrdom. And we have that from other religions as well. Like again, I mean, do Islamic terrorists sort of get cold feet when they see one of their compatriots die in a suicide bombing? I mean, maybe some do but a lot of them don't. So I don't I don't think there's any evidence for this claim that there's some sort of negative effect of one disciple becoming less likely to continue in the faith when another is killed. But there's even further problems with this. How do we even know that the disciples knew what happened to the other ones? Because we don't know, for the most part. I mean, maybe Peter and Paul where we have some documentation, but most of them, we don't know what happened to the disciples and if they were as tradition holds, scattered across the Roman world and even beyond, right, like someone to India or something, how would they know what happened to each other? Like, I don't I don't buy this assumption that they would have just known that maybe some, but that's another assumption that's in play here. Also this seems to be looking at the wrong end of the stick here. We're talking about maybe years, two decades later, when some of them might have been martyred, some of them were and others may have been martyred. But what we're trying to explain is the initial reports, the initial beliefs right in the days, weeks, maybe months after the resurrection, martyrdom hadn't happened then. And what we're trying to assess is what is the probability that the disciples would have come to the belief that Jesus had appeared to them and begin to teach that in spite of persecution in that initial condition? You can't say that those are independent because years in the future, some of them may have got cold feet when they heard about a different apostle being killed. That doesn't make any sense. The timing is off, right? We're trying to explain the initial reports and beliefs. If later some of them did get cold feet, it wouldn't change the fact that earlier on they had believed that, which is what we're actually trying to explain. For all we know, some of the disciples did get cold feet when they heard about others being martyred. How would we know that that's not the case?

James: There's a second argument which honestly just doesn't even make any sense to me. Like the Cold Feet argument makes sense. I just think it's implausible and under motivated. The second argument that they gave, I just don't understand.

Kamil: These are exactly the points in the argumentation where they could very easily look at what's actually happening in the world with religious people and actually get some data, get some background knowledge about how people function under these circumstances. But there's no discussion about it here.

James: I want to ask, did these disciples not think that God would protect them because it seems very plausible to me that they would. How many people do we see today who think that God will protect them from coronavirus and therefore they don't need to get vaccinated, even though there's no evidence for that at all in any of their texts, they just making these things up. But but these people die, right? They don't take precautions and they get it and some of them will die and have died on the basis of a belief that they've just plucked out of nowhere, right? That God will protect them of this sort of thing. So why wouldn't something like that not happen in the case of the disciples? We see that in other religious traditions as well that people believe God will protect them. People believe that they killed themselves, and then they're going to go up to the UFO that's coming to resurrect and save humanity from the asteroid or whatever it is in some of those cults. Why are we expecting that death is some sort of big disincentive?

James: The distinction they make between an empirical fact seems to be the sort of thing that philosophers debate about but ordinary people don't make a distinction between something that they know is true for whatever reason and something that they've seen to be true. It's just, look, they know that Jesus is Lord, right? They may have seen him, and that's part of how they know. But it's not the fact that they saw him itself. I think that part of it, it's that they knew that Jesus was Lord and that he'd risen and all that just as Christians today. That's what motivates them, irrespective of whether they think that they've had an experience. I mean, some Christians will say that they've seen something or heard something else. It's not clear that that itself is what's driving them, but they McGrews's want to tell us that that is absolutely critical and that no one would die for claiming a particular empirical fact to be the case unless they had really good grounds for it. But people will die for ideological beliefs that they don't have a good ground for. We have not been given any reason to think that that's the case or that that distinction meant anything to the disciples. So until I get some reasons for thinking that the distinction matters or was irrelevant to the disciples, I'm just going to say, what difference does that make?

James: if you want to interpret in a Bayesian terms, I don't think you have to but can, it's to say that, as we said before, if the prior was very low, you need a very likelihood to overcome that low prior. I think that that is a very profound insight, even if intellectually, we all know it -- as the doctor's case that I mentioned and many other cases -- people neglect base rates and so we're actually not good at doing this in a lot of cases.

Nathan: But the interesting thing is that the base rates are completely taken out of this text.

James: Well, that's the irony.

James: They say they say here that Hume was wrong to make in principle arguments against the resurrection because as they say here, that you need to "leave the high ground and descend into the trenches of engaging in specific historical events." Well, the thing is apologists actually, never do this or almost never do this for other religious claims, though. They only look at Christianity, and maybe there's one or two others that come up occasionally. The point is, though, that they love to focus on the details. They'll write thousands and thousands of pages on all the details of Christianity. But if you ask them about, say, Mormonism or all the other Messiah claimants or Hindu miracle performers and all sorts of other cases that I document, they have very little to say about them. They don't descend into the trenches. They don't go through the details of that again, most of them most of the time.

Nathan: no one should do as well. I hate it when people frame the sort of discourse in this way where it's like, well, for any crazy claim that certain groups of people have really committed to, expended all this intellectual effort on constructing like Martin Bailey defenses that you can spend your entire life trying to deconstruct and you were like, get through that. So if anyone makes any of these claims you've got to, then you know, like you've got to get a degree in like biblical scholarship, right? You've got to learn the original Greek. [...] I don't think anyone should reasonably have to do all this just to be able to conclude that they don't think someone rose from the dead when there's nothing in their experience that indicates it can happen [...] Sure, there's room for a more detailed analysis, but it's just so unfair to put this expectation on normal people.

James: Yes, I agree, and it's one that they won't bear for other belief systems as well. So it's entirely it's entirely self-serving.

Although they admit they don't accept this Bayes factor, James does provide a way to make the prior lower than that -- even accepting that God exists, wants to save humanity, and can do miracles.

James: this is something I just sort of thought of on the on the fly. So the argument is something like this, let's suppose that I believe God exists, and let's suppose that I believe he's going to take some sort of intervention to help with saving mankind. Now, I don't know why you'd think those things, but let's just stipulate them for the sake of argument. Now, I have no additional beliefs about what that action might be. Now, God can do anything that's logically possible, right? So the set of things that he could do to save mankind, which would include resurrecting any particular human who has ever existed, resurrecting any animal who's ever existed, resurrecting multiple people, performing any arbitrary miracle, not doing any miracle, moving the planets around like anything you could imagine. I mean, God could work that into his plan to make that serve his purpose, right? I mean, he's God. So the set of things that he could do to serve his purpose and give a message to mankind is effectively infinite. The set of things that the Christian is postulating that God actually did is just one, he raises Jesus from the dead, right? So we've got a prior of one over "infinity". (You know, in quotes, because obviously that's not a number.) So basically, that's a zero prior for or close to zero, as makes no difference for the probability that Jesus would be resurrected. And that's given that I believe in God and that God would intervene, but not having any particular belief about what God would do. So that's my reason for thinking that it's lower than 10 to the minus 43 because I'm just indifferent between any of the possible things. Your mileage may vary with that argument. I'm not sure I entirely believe it myself, but the point is that is it that hard to come up with reasons as to why it would be extremely low? God has no constraints on him. If I'm a Muslim and I believe very strongly that Jesus was only a prophet and that God wouldn't resurrect him. Maybe that gets me to 10 to the minus forty three, right? Hmm. But you just need a bit of imagination.

James: But what Plantinga is saying is that in order to get to like a belief in Christianity, you have to proceed sort of step wise. You have to start with like God exists. And then there's like conditional on God exist. Oh, God, existing God would want to make some sort of revelation of himself to mankind and then conditional on God wanting to make a revelation himself. [...] His point is that because those are all probabilities they all have to be less than one. If you multiply a bunch of numbers less than one together the number diminishes. I think it's illustrative to point out that even if you start with fairly high numbers, if you take point nine, for example, they're going to raise it to the power five, like point nine to the power of five. If you have five independent things that are all 90 percent likely you get, point five nine four. So obviously if it's less than point nine, then it diminishes more quickly. So you can quickly go from highly confident to actually not that confident, even if each step is fairly confident by having a bunch of steps. That's the key point Plantinga is making there, and I think that's a very good argument to be is sort of suspicious of this stepwise inductive or, I guess, Bayesian type of arguments.

James: In fact, this is exactly what you do from scam emails. I look at it and say, what is the probability that this person exists and conditional on that, what is the probability that they've sent me this email? Because as like, for example, if I've got an email that said it's from Plantinga, I know that Plantinga exists, but I would assume that it's not actually from Plantinga because he's probably not emailing me, right? Whereas if I got an email that says it's from Elvis Presley, I would say, Well, it's probably not from Elvis Presley, right? The fact that I've got an email claiming to be from Elvis Presley isn't going to overcome my low prior that Elvis Presley is alive because he died a long time ago. So it seems to me that although we may not explicitly do this in many cases, that is actually the appropriate way to do it is to consider separately, at least like conceptually separately, the probability that the person sending you the email actually exists like the Nigerian prince. And then given that that person exists, what is the probability that they are sending you this email?

James: they're saying that we don't have priors over people that we meet, basically. And I just think that's wrong. I mean, whether we mentally have something like that is another question. But the question would be like, is there a way that you could appropriately assign priors to make sense of inference? And I think it absolutely does. And that is how I distinguish between people claiming to be someone that I think is plausible and people making claims that are not plausible, right? What if you've got no way to make the distinction? You can rightfully describe that as a prior because it's not based on any specific evidence that you have about that person. The prior would be with respect to the factors prior to your particular interaction with that person's background knowledge, that would be relevant like, for example, someone claiming to be Elvis Presley. The fact that I would disbelieve isn't based on how persuasive they are or like, how good their outfit is or something like that. It's based on beliefs I have about Elvis Presley, which is prior to that particular meeting. how else could you describe that right? The McGrews want to say that that just isn't the thing. But I don't understand how they then make these distinctions. How do the McGrews explain the fact that sometimes we don't believe people when they tell us who they are or when they email us or something like that?

James: So they're complaining that Plantinga is pulled out this 0.9 from nowhere and is claiming that it's generous. Yeah. Now does that remind you of anything? Seriously? They have the absolute gall to complain about that after what they've done in this whole article. It's unbelievable.

James: it's disappointing because in principle, Kamil and Brian were talking about this, but in principle, I think you could use Bayesian techniques to elucidate some of the key points in the argument here. If it was done well and carefully, but it's unfortunately not. And so maybe I'll just quickly highlight some of the key aspects of this without going through everything we've discussed it that I find most problematic.

One is the fact that they are very unclear about what the methodology is, that they're even trying to apply here. They talk about Bayesian techniques and they talk about the likelihood ratio. But then they, as we mentioned many times, keep flipping back to talking about the low plausibility or the prior probability of many of the things that they don't want to consider that, you know, they're <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"><semantics><mrow><mo>∼</mo><mi>R</mi></mrow><annotation encoding="application/x-tex">\sim R</annotation></semantics></math> hypotheses rather than resurrection, whereas they don't address that at all with respect to God or the proposition that God would want to raise Jesus from the dead. But it's not clear why they should be persuasive to anyone else if they don't actually present objective considerations like models or base rates or other things. So that the whole methodology is, I think, very unclear.

A second key problem is that the arguments that they give in favor of the key facts that that's the women and the disciples and then the Pauline conversion just relies on basically taking the the New Testament at face value and accepting every claim that it makes. And if you're going to do that, just read the part where it says Jesus is God and was raised from the dead and be done with like it's so much more honest and quicker that going through all of this, no skeptic is going to acknowledge all of these things as being veridical and all of the original authors and based on eyewitness testimony and all this sort of stuff that that they are leaning towards or explicitly arguing for and then make really, I think, problematic appeals to very selective scholarship and pooh poohing the textual analysis, critical analysis stuff that they don't like, but then appealing to it when it suits them.

So the third point here is that they when considering the relative explanatory power of resurrection versus not resurrection, they often didn't consider many not-resurrection type arguments. So many of those sorts of things that say Kamil and I would advocate for weren't discussed somewhere were but a lot weren't. And even more significant than that, They didn't really say much of anything about the actual explanatory power, like the probability of the evidence given the explanation. They mostly just said the naturalistic explanations were improbable, like low prior, which doesn't say anything about their explanatory scope, while at the same time saying almost nothing about the explanatory power (the probability of the evidence given resurrection) about their own proffered explanation. This is most clear, I think in the case of Paul, where it's completely unclear how a resurrection is supposed to explain why Paul was converted because they just completely separate from each other. God could appear to Paul, whether or not Jesus was resurrected, and why would God want appeared to Paul anyway? Like, what does that have to do with anything? They just don't address this so that they're really bad at actually trying to explain how their explanation is a better explanation, how their model is a better explanation than competing explanations.

And I think the final point that I wanted to make is the issue of independence, which is absolutely critical to their argument because most of the, really all of it comes from multiplying low numbers together or high numbers, depending on which way you look at it, and they justify that by the independence assumption that the women's testimony is independent of the disciples testimony, which is independent of Paul. And then furthermore, that all of those 13 disciples testimonies are independent of each other, and the justification for this is just ridiculous. Basically, they say that it's actually independence overestimates the evidence against them, like it underestimates the strength of their case because first of all, the disciples would get cold feet or be likely to get cold feet upon seeing one of the disciples be killed or martyred for their cause that that would actually cause them to be more skeptical than they otherwise would. And of course, they cite no evidence for that. The other reason that they gave is just that the best explanation for why all of the disciples became convinced is because they actually had good evidence, which I don't even understand how that's an argument -- it's just reasserting what they believe. So the point is one of the absolutely key assumptions behind their entire approach, which is the independence of these key facts here is just defended in a, I would say, pathetic way, like the arguments are just really ridiculous, and that undermines the entire premise of what they're doing.

James: So overall, it was difficult to read. It was really frustrating. It was too long. The arguments were mostly quite bad. They don't fulfill their promise of actually comparing the explanatory scope and the conditional probabilities of the resurrection versus other hypotheses. And this is a consistent failure of these sort of apologetic studies that claim that they're going to make a comparative analysis but just do a really shoddy job of it and don't seriously consider what skeptics would actually believe and what arguments they actually make. And don't try to give actual reasons for why the explanations that skeptics offer are bad. They just sort of assert that they're improbable and not take it seriously and not try to argue why their explanation is better. So, yeah, I think it's really poor scholarship, and I hope that you found some of our remarks to this effect for the last nine hours of interest.