Gravitational Attraction

What would happen if two people out in space a few meters apart, abandoned by their spacecraft, decided to wait until gravity pulled them together? My initial thought was that …

In this YouTube episode, Bad Apologetics Ep 18 - Bayes Machine goes BRRRRRRRRR I join Nathan Ormond, Kamil Gregor, and James Fodor to discuss Timothy and Lydia McGrew's article in The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology entitled "Chapter 11 - The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth".

It's 9 hours long, but I am only on for the first 7 hours. This isn't a complete log of everything said, but I tried to include the main points. I also started with a transcript, and edited it for clarity (e.g. removing ums, and repetition) but there may still be some weird typos from the computer generated transcript that I didn't catch. I will try to quote Nathan, James, Kamil and myself if it comes from the episode. All other text is mine, commentary either at the time or sometime afterward.

The parts of this document are here:

And the link for the full video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/yeCBpO7pSRM

The main issues are:

Nathan opens up comparing the methods in this paper to looking at problem about gremlins in ones closet.

Nathan: they basically compare the likelihood of the evidence given the hypothesis against the likelihood of the evidence given "not the hypothesis". And the reason I think that's a problem is because there's a bunch of risky claims like that. You know, the likelihood that there's noise coming from my attic, given that there are gremlins in my attic is like pretty high, right? But. That if you kind of flip that around and make it so what's the likelihood that gremlins are in my closet given that there's noise, it's not actually that high and they don't really seem to look at it that way.

By looking only at the likelihoods, one might contend that it is highly likely that there are gremlins in my closet given some noise in my closet because

or the likelihood ratio

Essentially, if you ignore priors you can argue the most ridiculous things. In McGrew's seminar here he actually makes that point -- that you need both the priors and the likelihoods. Too bad he doesn't follow his own advice in this paper.

Kamil points out that they don't provide alternative explanations, the proposition \(\sim R\equiv\) "Jesus was not resurrected" is not really fleshed out, so it's hard to say what any of the probabilities are. Also the proposition \(R\equiv\)"Jesus was resurrected" is hard to deal with if you don't specify what that means. The expectedness of this proposition will depend on our background knowledge, which includes the laws of physics, so if \(R\) entails violating those laws or not then you run into problems defining what it means.

Kamil: it's very difficult to explain what exactly you expect on hypothesis that Jesus's body didn't obey the laws of physics. If you start specifying it, then you run into the problem of baking the data -- the evidence that you are trying to explain -- into the explanation itself

James: And I made this point before that just because Jesus was resurrected, actually nothing follows whatsoever about who Jesus would appear to or let alone that Paul would be appeared to, but we'll come to that, but they don't really discuss this at all. It's just an assumption the resurrection explains all the facts without even addressing it. And then in opposition to that, they don't even pick a specific hypothesis or theory. They just talk about everything else, which makes it very hard to actually compare properly.

Brian: So my first thoughts on this is and we'll see a number of these points coming up, is that I find a lot of commonalities in different arguments that try to use Bayes in this way to support specifically religious arguments.

- Badly defined propositions, and I think that's what Kamil and James were getting at -- that they don't specify what these propositions actually mean or what they predict.

- What I like to call lack of imagination, and that's basically just not really taking seriously all the various alternatives. There is the denominator where you're simply dividing by all the different alternatives. So if you're not doing all the alternatives, you're going to have inflated probabilities because they should be scaled down the number of plausible alternatives.

- They never deal with priors. Well, I'm sure we'll get to that

- The independence assumption, and I'm sure we'll get to that as well.

- Arbitrary numerical values where we'll see that they just are making up values up off the top of their head without really much justification.

And then you can combine all those into a soup that makes a lot of this analysis kind of a mess.

James: maybe just to clarify a point there, so in using Bayesian approaches that the McGrews are doing a couple of things here. One is that they are describing their credence -- their degree of belief -- using numbers that have to obey the probability axioms that you mentioned Nathan. So that's fine. That gives a constraint on your reasoning and argumentation. But by itself, it's not actually clear what argumentative value that's going to have. So for example, if I say I hold the credence of 99.99 the God raise Jesus from the dead. And I could even go off and then calculate all the things from that by combining with other probabilities. That in itself doesn't actually tell you anything about what you should believe. I've just described my own subjective beliefs. That's what Bayesian reasoning involves -- it is understanding probabilities as descriptions of credence, as degrees of belief. So I think that there's an issue in saying all they just making up the numbers, it's actually OK for them to just pull the numbers out of wherever if they're just describing their own degrees of belief, right? But the question becomes, should I take that seriously? Do those numbers mean anything to me, or should I update my answers on the basis of those numbers? And if they're going to make that argument, they need to give us a reason as to why I, who, you know, have a different set of beliefs and different evidences that I should take those numbers seriously.

Brian: So, so my critique about that kind of arbitrary numbers is they don't make really much effort in constraining them.

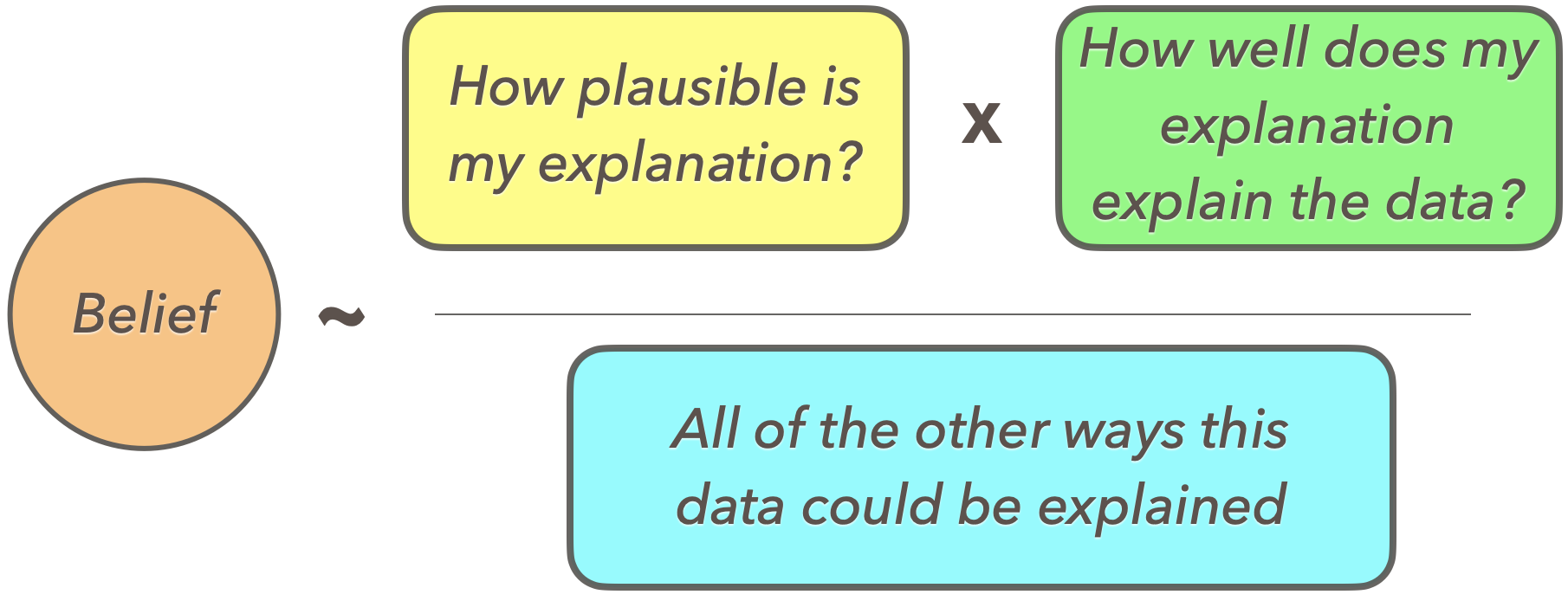

I see probability coming from kind of the formalism that E T Jaynes sets out. He has a set of axioms that that he uses to derive the laws of probability.

My feeling is that that aside from the kind of quantitative aspects, it gives a nice structure to an argument where you can see where your inference might be coming from and what it might be affected by. You have to list off all your assumptions all at once, and in that way, you put everything out on the table and and someone can say, "Oh, look, this term I disagree with" and it lets you weigh different possibilities. It provides a structure where you can see how any new evidence might affect particular values. And that's where I see the kind of value in this. It's not the specific numbers that you're going to come out with, it is the structure that you use.

Kamil: I perceive it as a really useful tool for structuring thought and for avoiding a lot of the invalid inferences that people make in objective reasoning. And one thing that it does really well is that it solves one of the issues with the argumentation to the best explanation. In argumentation to the best explanation, usually the idea is that you have a number of criteria of what constitutes a good explanation and that you're going through various competing hypotheses and you are trying to essentially to score them in terms of how well they perform on that criteria. Things like explanatory power, plausibility, exploratory scope, explanatory value, simplicity and others like that. But then the issue is it's usually not the case that the hypotheses either fits the criteria or it doesn't. That's usually a degree. So there is a degree to which a hypothesis has plausibility. There's a degree to which a hypothesis has explanatory power.

I see value in Bayesian reasoning in that it gives you a good method to take these various explanatory virtues into account all at once.

James: I actually don't think the Bayesian approach as much at all to this article, you could get rid of it, and most of it would just be the same. Kamil: If you watching this and you don't understand Bayesian reasoning, first of all, you apparently are not smart enough to get saved and go to heaven, but also that doesn't doesn't really matter. This is not the most technical piece of literature. Brian: I think mostly because they never really deal with priors, and so once you're not doing half of the equation, then it really doesn't matter.

Later in the discussion, James points out that they do use the priors, just inconsistently.

James: [on Hume]. I don't think it's trivial now, even if you know, Bayes because people make this mistake all the time. Like with the the classic studies they do with doctors asking them about what's the probability that someone has the disease, given that they've tested positively when there's a high false positive rate? Doctors consistently ignore the base rate. And I think that you can interpret what [Hume] is saying as you've got to consider your prior and your likelihood. And if the prior is really, really low, like for a miracle, then you've got to have really, really strong evidence. You can't just be enamored with what evidence that looks strong if the prior is low. So I don't, even if that's all Hume is saying and that's disputed, I don't think it is a trivial result. I think it's a very important result. And in my opinion, he delivers that in an eloquent and memorable way. So yeah, I don't get the criticism either.

Kamil: I think there is just some weird, like idiosyncratic thing about how apologists argue, and it's that when they are trying to argue against like a body of work in a specific field of science, they always go after the person who first proposed it. Like, there is a lot of people who argue against what Charles Darwin wrote, and they think that if they poke holes in that, they somehow like, dismantle 150 or 200 years of evolutionary biology. The same is every time I see someone critiquing the documentary hypothesis and old testament studies from like a Christian apologists point of view, they always go after Millhouse. Then they don't engage with people who write about it today. And the same goes with Hume, right?

Brian: I don't like psychologizing these sorts of things, but I think the way theists think in terms of authorities, they see authority giving truth, right? They find it very hard to imagine anyone who just doesn't care about authorities. It's like it doesn't matter what Einstein said, it's just what the equations say that matters. And so attacking Einstein is not going to move us much. But they see it as the truth, the idea tied to the person because that's the way they think. Because that's the way that religions are structured.

Nathan: So I think that this is what Brian was talking about in terms of lack of imagination because I can think of a ton of things that might occupy that probability space, right? Other than theism. So I mean, aliens, right? Maybe like juvenile aliens who are just messing around and wanted to like trick these random primates on some planet could they not do it? And then I do think it is important because within that probability space, the key thing is it might occupy a chunk. And it was interesting because I asked Vi about this, and we both had wildly different like beliefs about this because I thought that theism was maybe like quite a chunky part of that space for myself, but for Vi, it was like quite a bit lower.

Brian: Every time they say \(T\)=Theism, I find I just try to imagine every kind of crazy God that I can imagine -- Stephen Fry's, evil God, Cthulhu -- what's the probability of Jesus getting resurrected under any of those? It's basically zero or Zeus, right? It's because they don't take these seriously, and they've already assigned them really low priors, but they're not going to directly address that. They're just sweeping those under the rug. And so this is exactly what I was talking about in terms of lack of imagination, but also badly defined propositions. Theism isn't well defined which makes it impossible to pin it down in any real way.

Kamil: They start bringing in implicitly assumptions from Christian theism specifically, or from a subset of it, let's say, classical theism. And I think it's much easier for them to get away with it, doing it implicitly because they use "capital G" God, which is normally how the Christian God is written. This is why I'm personally very careful to always use that name the term Yahweh, because it brings to the attention that we are talking about a specific deity which has specific mythological baggage. We're not just talking about any God.

James: And later on in the article, they actually specifically mention the example of Zeus resurrecting Jesus. And they basically just dismiss that as saying, "Well, there's no reason that Zeus would have to resurrect Jesus, right? So even if it existed, it wouldn't explain the evidence". My question would be what reason do we have thinking that Zeus has more reason to resurrect Jesus than Yahweh does? It actually seems to me that Yahweh has a lot of reasons to not resurrect Jesus because of the fact that the apologists usually mention that resurrection is supposed to happen at the end of the world, and the Messiah is not supposed to be resurrected, and the prophecies are not fulfilled in the Old Testament that the Jews talk about, whereas none of that seems pertinent to Zeus. I mean, Zeus does what he wants like, why would he not resurrect Jesus? I mean, he'd just do it for a laugh. You know, Zeus is always causing trouble and mischief, so I don't see why he wouldn't want to resurrect Jesus. Seems that the probability he would resurrect Jesus is higher than the probability that Yahweh would resurrect Jesus.

James: so there are actually so many options here, just to summarize, we've got

- Zeus and other god

- ghosts

- sorcerer

- aliens

- some unknown natural principle

- reincarnation

I could just make things up all day about what it could possibly be if we don't have any constraints.

And the question is, if we're going to actually do a Bayesian analysis to compare explanations, what non question begging reason do we have for saying that God is more likely to resurrect Jesus than any of the other ones that I just mentioned? I have not heard a clear answer to that question that doesn't already appeal to like a bunch of stuff in the Bible or whatever, which is what I mean by question begging. Why should we accept that?

Kamil: That would circle back to the issue that I mentioned initially of just defining our explanation in terms of the evidence that you're trying to explain. If you have a set of data and all that you're saying in the explanation is that "there are ghosts and they want to produce this sort of data". Now, first of all, there isn't really any constraint about what is a ghost, what it can do. It's really vague it doesn't say much. So it's really difficult to to estimate what's expected on the ghost proposition, right? Which I think is directly analogous to the resurrection because you don't know what is a resurrected body, what kind of properties it has like, does it interact with light? Does light reflect from it back to your eyes so that you can actually see it visually? It does, except when it doesn't, and it has solid substance, except when it doesn't like when he passes through locked doors. So that's one problem. And the second problem is the ghost that wants to do exactly what the evidence is, right? Well, then you're not explaining you're just restating the data. James: That's what theists explanations always are. They say "God just wanted to do this" that's all the explanation is.

James: But I think it's actually important to draw this out, that's what you get when you appeal to God's intentions or actions when you're explaining anything because there're no constraints on what God can do, and it's unclear where you get any constraints over what God even would do unless you have some sort of actual theology to appeal to, to say he would do this or would do that. So I think at the end of the day, you just get a list of "God did it" and he did these things right and that just all of the things that are necessary for your data like, Oh, God raised Jesus from the tomb, removing his body from the tomb. And then he appeared to the women so that they saw him and then the disciples, and then he appeared to Paul. That's just basically very close to a list of the data to be explained.

Kamile: But it's very, very important that when we explain evidence in terms of people having intentions, it's very important to to ask the question how plausible it is that the given people, in the explanation would have the intentions that they are hypothetically hypothesized to have. It's really, really trivial to imagine hypotheses that explain a set of historical data in terms of specific people having specific intentions, which are nevertheless really implausible given our historical background knowledge, or even just given simple things in our background knowledge, such as some general features of human psychology.

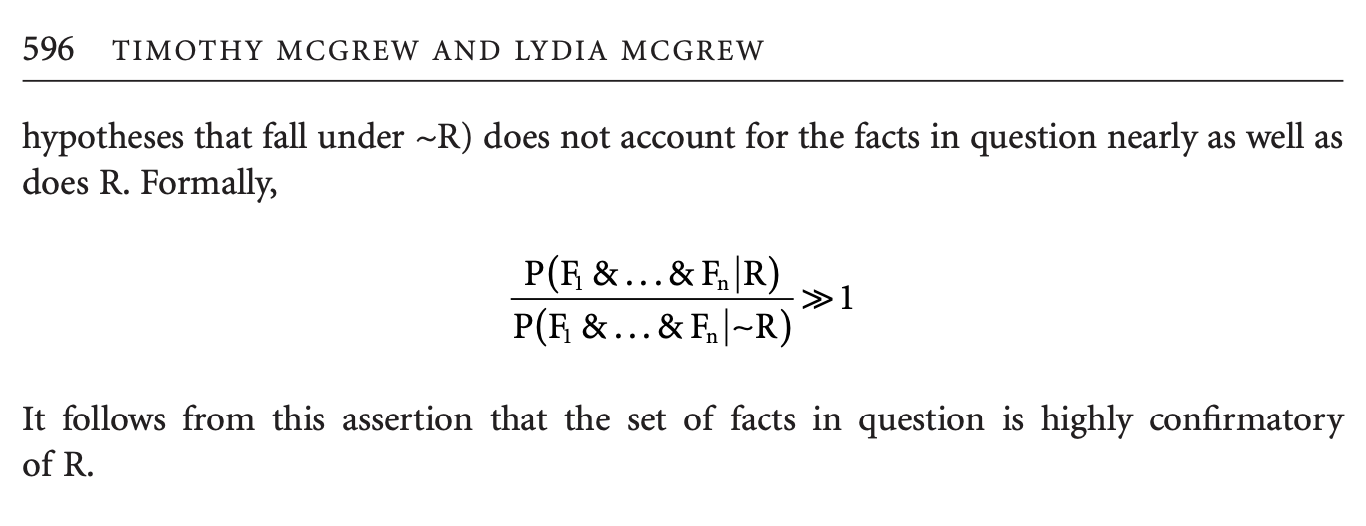

Brian: One of the points I was thinking of when Nathan put up the form:

So one of the problems with this is that you can have an explanation that doesn't fit the data quite as well, but it's far more plausible and that will outweigh in a Bayesian sense something that explains it really well, but it's implausible.

with \(P(E|R)>P(E|\sim\!\! R)\) (an explanation that doesn't fit the data quite as well as \(R\)) but \(P(R)\ll P(\sim\!\! R)\) ( it's far more plausible than \(R\)).

And so by ignoring the priors (\(P(R)\) and \(P(\sim\!\! R)\)), which the McGrews do, they pretty much throw out that entire part. For example, you may think that aliens doesn't explain the data all that well, but they're far more plausible than any kind of spiritual or supernatural explanation. But then what it does is you then have the argument about priors. I think this happened in the conversation with Max Baker-Hitch and Calum Miller It got to the point where they admitted that the naturalistic explanations were reasonably plausible but then we have to back it up to the evidence for theism directly.

James: The point there is that there's no priors there, right? So they're actually just saying that the evidence is confirmatory for the resurrection over, not R. Now what Kamil was saying is that they're ignoring priors, and this is the sense in which they're ignoring priors because there's no prior probability. However, they are not consistent with this because, and we've already seen an example of this and we'll see it more, when they address naturalistic alternatives they say, this is implausible. Yet they don't say that it wouldn't actually explain the data. They just say it has a low prior, they say low antecedent probability. So they are completely inconsistent with what they actually do in their argument. So I actually think that they do consider priors, but only when it suits them.

Kamil: what I want to say is that this is an argumentative strategy that you see all the time in papers that use Bayesian reasoning. They will say we are not going to be looking at intrinsic probabilities. We are just going to compare expectedness of evidence. And the idea behind that is that, first of all, it's really, really difficult to establish probabilities in general. And second of all, the argumentative strategy is very often to show that the likelihood ratio is just so high in favor of one hypothesis that in order to overcome that, we would have to imagine a really, really high difference in the prior. I think this is perfectly fine if you stated in the paper that this is what you're doing explicitly.

Lydia McGrew in a separate video admits to doing just that -- if you can demonstrate the likelihood ratio is high enough, it can overwhelm any reasonable prior. So, if they are doing this, then they should state it up front and also never talk about the plausibility of any competing hypothesis because that would be irrelevant to this approach.

James: They've got conditional on \(R\), which is the resurrection hypothesis and then the same evidence, but conditional on not \(R\) now. I think that that's a terrible way of trying to do this because I mentioned this before. The way that you would typically do Bayesian model comparison is by comparing one model to another. And when I say model here, I mean, like a theory. So like the resurrection would be a theory. An alternative theory would be something like Camille's explanation or my RHBS model or, you know, different a combination of both. They're not necessarily mutually exclusive, but you consider one model and then compare its explanatory value or, in other words, the probability of the evidence given that explanation and compare that to the resurrection. One trying to compare it to all of the others. I mean, in principle, like so "not \(R\)" (\(\sim\!\! R\)) would technically include every other explanatory option. But the problem with trying to do that is that it's so unconstrained because it's literally just everything that's not the resurrection.

As we'll see later, there's actually no constraints on what they can argue against. So they'll pick whatever counterexample that they like, like naturalistic theory for whichever part of that and argue against it when it's convenient. And then when a different one is convenient, they'll argue against that because it's just "not \(R\)" like anything will do. And I think that this often leads to inconsistencies and it gives the impression that there's not really any competing explanation because they're not considering a competing explanation. They just sort of picking from the set of every possible thing that's "not resurrection".

One of the strengths of Bayesian reasoning is it that it forces you to write down all of your assumptions up front, and all of the models that you're comparing it to. Unless you truly have only two models, you just don't set it up like

especially when "my model" is not well constrained, because the terms contain too many parts that you can either sweep under the rug or accidentally overlook because they are lumped into too big blocks.

Kamil: That's like a general problem in things in a Christian apologetics. One of their objections against alternative hypotheses is that they don't explain all of the data, they only explain some of the data. But the thing is that very often the explanations are intended to explain exactly some of the data. They will say we can reject the swoon hypothesis because it doesn't explain the appearances and we can reject the hallucination hypothesis because it doesn't explain the empty tomb.

That's why James's RHBS model has four parts -- reburial, hallucination, memory biases, and socialization -- because it's likely to be multiple interacting phenomena to explain something as complex as the birth of a new religion. But if apologists look at it one-by-one, they'd say the hallucination doesn't explain the empty tomb while reburial doesn't explain the appearances, and they'd think they were arguing against the model when in fact they aren't. They could rightly complain that the conjunction of 4 different things is implausible -- the product of their probabilities would be lower than any individual one -- but each of these is so much more plausible a priori than a resurrection that this is not really an issue. Every one of those parts concerns phenomena that we know happen, and in some cases (e.g. biases and socialization) happen frequently.

Brian: I find that this way of formulating it kind of piles a bunch of things into the "not \(R\)" part -- and even the "\(R\)" part -- that they're not really explicitly doing. Kamile said that they're two important parts of Bayes theorem but I would actually state that there are three. I gave a TEDx talk where I going to try to give an intuitive explanation of the structure of Bayes theorem: a belief in a particular explanation should scale with how well that explanation fits the data (called the likelihood), it should also scale with how plausible that explanation was before you saw any data (the prior), and then the third part is the belief is scaled down by essentially all of the alternatives. So the problem with the phrasing it in this "\(R\) vs "not \(R\)" comparison and not breaking it out into all the possibilities is that you end up not being specific about your alternatives of doing things like Kamile said, like ignoring things where an explanation is designed for only part of the data. It makes it a lot less constrained. And I think if they broke it out, they would see it would be less constrained.

Kamil: So if you are a Christian first and you want to maintain that, it's really, really plausible, given some general considerations like philosophical and theological considerations that a God would want to raise someone like Jesus from the dead. Then it becomes really, really plausible at the same time that someone like Jesus's disciples would conclude that Jesus was actually raised from the dead, even though he wasn't, precisely because they also had access to those philosophical and theological considerations, right? Like if Swinburne is really correct, that it's very, very plausible that, for example, someone like Yahweh would want to raise someone like Jesus from the dead, then no wonder that someone like Jesus's disciples were falsely convinced that Jesus was raised because in their mind, it was just so damn plausible, right? So they just formed a false belief based on that high possibility. This is again like a fatal flaw.

Well, and I think that the problem is exactly that. Christian theists want to have it both ways. They want to say at the same time that the plausibility of the resurrection is really, really high. So we don't really have to worry about that huge difference in plausibility ratios. But at the same time, the evidence that the disciples had access to must have been really good in order to overcome the unexpectedness of something like the resurrection on their existing religious milieu. But yeah, I think there is a massive tension between those two ideas, either it's plausible -- so it's likely that you would be falsely convinced of it -- or it's implausible -- in which case that is the problem with the prior probability.

Kamil's point is worth pausing and understanding what it means for apologetics for the resurrection.

Nathan follows this with exactly the problem with looking at likelihood ratios instead of posterior probabilities.

Nathan: the fact that they're ignoring the base rate rate seems to mean that you kind of lose all of the benefit, in my view, of doing that Bayesian analysis. That example James gave before of doctors diagnosing people and the kind of heuristics that we use. So for example, if you say you've got a positive test for HIV in the UK or something, you might think, "Well, given that I'm a doctor, right? And this person is here presenting with these symptoms and they've got a positive test. And it's that evidence is really, really likely on the hypothesis that they've got HIV vs the hypothesis that they've not got HIV" and it would actually win out, I think, on this analysis. But when you take into account that base rate, which is the number of people with HIV in the UK, which is really, really low like naught point naught naught naught one percent something, then boom. All of a sudden the probability of having HIV given the positive test it's something naught point four or something.

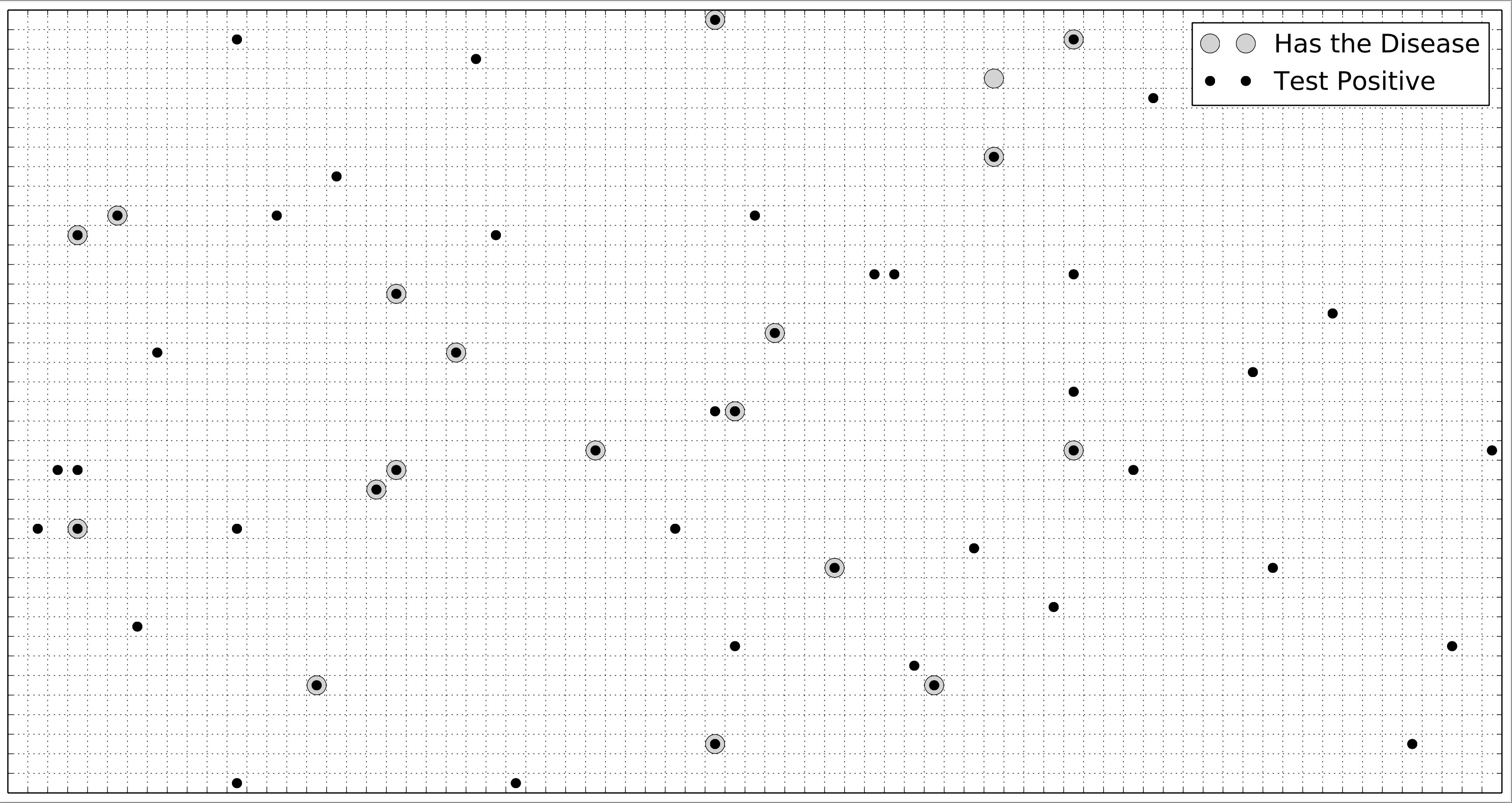

This is exactly right. If you ignore the priors (base-rates) then you can convince yourself of a false claim following our (flawed) intuitions. The calculation would go as follows. I use small numbers to make things more intuitive. The disease is 1 out of 200 in a population of 3000, and we have a test that is 99% accurate. You test positive, and want to know whether you should think you have the disease.

The Bayes' Recipe proceeds as follows:

In our case we have

2. Write the top of Bayes' Rule for all models being considered

The "models" in this case really is binary: you either have the disease or you don't. Unlike in the case for the resurrection where there is more than one way to have the model "resurrection" happen and more than one way for "not resurrection" to happen. The top of Bayes theorem has the likelihood and prior for each model, so we'd have:

The likelihood terms come from the test

So the top of Bayes for each model would be

Which means that if you have a rare disease, you are very unlikely to have it even given a 99% accurate positive test for it! This is a seriously unintuitive result, so it is helpful to visualize it in another way to build your intuition. One way to see this result is to visualize it.

The disease is 1 out of 200 in a population of 3000, and the test is 99% accurate. This means about 15 sick people and about 2985 healthy people. If all of the sick people test positive, and 1% of the healthy people test positive due to the 99% accuracy, we would have 15 sick and 29 healthy people who all test positive.

The disease is 1 out of 200 in a population of 3000, and the test is 99% accurate. This means about 15 sick people and about 2985 healthy people. If all of the sick people test positive, and 1% of the healthy people test positive due to the 99% accuracy, we would have 15 sick and 29 healthy people who all test positive.

This effect depends on the rarity of the disease (the more rare, the less likely) and the false positive rate (the number of healthy people who test positive anyway). This will vary depending on the disease and the test, but can lead to this unintuitive result, and thus can lead one to make poor medical decisions. It also means that by ignoring priors one opens oneself up to these kinds of errors.

I did not earlier that Lydia McGrew in a separate video justifies ignoring the prior because they supposedly demonstrate that the likelihood ratio is so high as to admit no reasonable prior, even if low. They don't, however, state that in this paper and they aren't consistent in their approach to priors as James points out earlier.

Kamil: Well, I think the this is why we said at the beginning that framing this article in terms of Bayesian reasoning is superficial. For the reason that you can just take the equations and the Bayesian fluff out. This is essentially very similar to, for example, of what Mike Licona is doing. Mike Licona is not a Bayesian. He goes for good old argumentation to the best explanation. The conclusion that he gives is that the resurrection hypothesis has much better explanatory scope and explanatory power. But when it comes to plausibility, he says, "A historian cannot, in their professional capacity, evaluate whether miracle took place or not. So I'm just going to leave the plausibility cell in the table of hypothesis virtues empty. So I will be essentially agnostic or undecided about whether the resurrection hypothesis is plausible. And he says, "Look, we have all of these alternative hypotheses that don't have exploratory power, or they don't have explanatory scope or they don't have plausibility. And then that is mine that has explanatory power and explanatory scope but it has not been established that it has low plausibility because I just didn't do anything with plausibility. So that's the best explanation, right?"

And the obvious objection against that is, if you don't do anything about plausibility and if you're essentially agnostic about whether it's high or low, then you should not say that it's the best explanation. You should say it's unknown whether it's the best explanation or not, because if it's the case that the plausibility is low, then it's a worse explanation and if it's the case that it's high, it's a better explanation. He doesn't use Bayesian reasoning, but the structure of the argument, I think, is very, very similar. And that just shows how, superficial the Bayesian approach is here.

Kamll: there's a really interesting interview that I actually did review on Doug's channel, and that's Lydia McGrew having a conversation with AJ Thompson. And in that interview, she says explicitly, "Look, when we started working on this chapter for the Blackwell's companion to natural theology, we realized very quickly that unless we can establish that the Gospels, were written either, by eyewitnesses themselves or they were sourced by eyewitnesses, then it's actually very, very difficult to establish that this ratio of expectations on the evidence is very high."" Because, obviously, if you believe that there were people in the first century who were sincerely convinced that they lived with the resurrected Jesus for 40 days and that he talked to them, they touched him, they saw him eat fish, etc... Then those kinds of experiences are going to be very, very difficult to explain on the naturalistic hypothesis. But the naturalist is obviously going to explain those data points, like the contents of Acts 1, as not being people who had those kinds of experiences in history in the first place but by positing that what Acts 1 depicts is a literary creation that does not correspond to anything that happens in history.

Brian: I think this one of the things that becomes clear here, and they could have dealt with this in the Bayesian framework if they wanted to, is what counts as data. So they have something like a claim that "Jesus ate dinner with the disciples after the three days" That's the data, or what they are taking as data. Whereas really, the data is we have a written document written 50 or so years later that has this story. And so it's a claim about that -- a text. And so you can put that into that formalism if you want to, but that's not what the McGrews are doing. This sentence in the paper is essentially saying, we're going to ignore the text and just count as data, literally, the claims that are there in the story. And if you're going to do that, you may as well just say, well, then the data is, "they said that Jesus was resurrected" and we're done with this argument.

Kamil: it's definitely the case with Brian said that when apologists read the passage that says that Jesus ate with Jesus with his disciples for 40 days after the resurrection, then the date relevant data is that there were people who experienced Jesus living with them for 40 days, right? Well, actually what the data is that there is a text that says that. And in this case, that's actually only in acts, right? That's not found in any of the documents that would be independent from acts, I think. [...] it's like a two step approach to this specific apologetic where they start. Like the step one is to actually establish that the Gospels and acts are historically reliable so that then (step two) they could treat the passage, saying that Jesus lived with his disciples for forty days as meaning or as implying that there actually were people who experienced that. [...] But the problem with that two step process is that assessing the historic reliability of the documents, I think is itself going to be conditional on the content of the documents specifically on them containing these kinds of miraculous claims, right? Like if you are a historian and you are trying to assess whether a document is historically reliable. One thing that is, I think should be at least somewhat important is evaluating what the document actually says. You cannot be just limited to external considerations like what is the attestation to the authorship by the early church and stuff like that. You have to actually look at the content of the document. And no historian probably would conclude that an ancient document that contains so many, let's say, fantastical material or material with very low prior probability counts as historically accurate. [...] any historian that finds a text which says that someone walked on water is probably not going to think that the text was actually written by people who were there to see it.

James: it's bizarre to say that we can assess the reliability of a text putting aside all of the non-plausible stuff and say, well, there's real places and real people and other stuff mentioned here. So therefore, all of the stuff that seems miraculous or seems to seems implausible or that would count against its reliability just sort of gets a pass. That isn't, as Kamil says, how historians assess any other document

James: I'm not necessarily disagreeing with the fact that the arguments from silence are pretty tenuous. I'm highlighting that because we're going to later that when it suits them, they deploy arguments from silence a lot, arguing against hypotheses that they don't like. So that's another one just to bear in mind.

James: Whenever the naturalist or just the skeptic about the resurrection postulates something, you know, Joseph of Arithamathea reburied the body or there were tomb robbers, or that there was a hallucination or whatever it is. They'll say, "Oh, he's got no evidence that that's just ad hoc". And then this is similar to, "oh, you know, we can't speculate about the intentions of an author". But then they feel free to speculate about what God would want to do about resurrecting Jesus and about setting him to appear to Paul and other things like that. So I mean, what do we have more basis for speculating about -- what people would do or what God would do? It's just seems entirely inconsistent to me. Plus, no one observed the resurrection. That's an unobserved postulate, right? The point is that the resurrection best explains the data, according to them. So why can't we postulate unobservables that explain the data?

James:How do historians usually react when they find a text which seems to correctly prophesy about an event that occurs in the future? What's the usual inference that's made there? Kamil: Well, they say that's amazing because we can actually date at the text really well. We can establish that it must have been written after the fact that it's prophesying took place, right? Brian: Isn't that circular, though? I'm just trying to take their point here. James: So they claim to date the Gospels to before AD 70 on the basis of fulfilled prophecy is just too assume philosophical naturalism. Now, whether that's true or not, I'm just making the point that they want the text to be treated like other historical text, right? That is how historians would treat any other historical text where there was something like this in it. So which is it? Do they want them to be treated special or do they want it to be treated like any other?

Kamil: Every single time when we see in ancient literature, these things that look like prophecies actually taking place, like coming true, and we can date the text using independent evidence we always find out that it's an accidental prophecy. [...] based on that background knowledge based on the knowledge that every single time we've seen something like that, it turns out to be an accidental prophecy from independent evidence. We can establish that this is probably going to be the case as well, right, and that's not a circular. That's not assuming naturalism, that's not having an anti-supernatural bias. That's taking into account background knowledge, when we assess evidence for a new claim, which is exactly what Bayesian reasoning is.

Kamil: One thing that people don't appreciate about early gospel tradition is that everything that we can actually evaluate, everything that we can actually check about that early tradition turns out to be wrong. So, for example, we can establish it's not the case that the gospel of Matthew was written first, we can establish that the Gospel of Matthew was not originally written in Hebrew -- it was originally written in Greek, even though all of the early Christian authors who comment on that universally say that it was originally written in Hebrew and they believed that probably because it's a very Jewish Gospel in terms of what it says. That led them to believe that it must have been written in Hebrew and there may have been some other reasons -- that it gets complicated. So given that the early church tradition has a really bad track record when it comes to things that we can actually establish, I think that massively lowers our credence. If they get everything else wrong, why should we trust what they say> James: What you're telling me, Kamile, is that the early Christian writers didn't know when the Gospel of Matthew was written, who wrote it, what order It was written relative to the other Gospels, or even what language it was written in? But they still knew enough about all of the other details to confirm that it was trustworthy, and that it had eyewitness testimony behind it and all of that.

James: "Our point is not that these discoveries demonstrate the accuracy of all other portions of the Gospels." OK, fair enough. It doesn't. Rather, "it is the common sense principle that the authors who have shown to be accurate in matters that we can check against existing independent evidence deserve within reasonable grounds the benefit of the doubt when they speak of matters of putative public fact that we cannot at present verify." I think that's a completely ridiculous principle because we don't just assume that because there are certain things that people say are accurate, that therefore, you know, probably everything that they say is accurate, like, imagine applying that principle to books of works of fiction. Well, you know, then they go to Paris and visit the Louve. And, you know, as they mentioned, Churchill and World War, you know, those things are accurate. So you know, they must be like, Harry Potter must be real, then. Just because real places and people are mentioned in Harry Potter doesn't mean that it's real. This seems to be a ridiculous principle.

Kamil: Maybe to disagree a little bit, this principle would definitely hold when it comes to evaluating other ancient texts, especially texts of a historigraphical nature by contemporary historians. So when historians are trying to assess the reliability of the text of some account, they look for whether the author gets historical details roughly correct in cases where we can actually establish that established independent of the text. And if it's the case that they do, it's reasonable to believe the other things that they say. [...] But it's important to realize to at least two considerations First is that this kind of reasoning is motivated by pragmatic factors more often than not, because it's just the case that we have so little surviving literature from the ancient world, especially solely to surviving historiographical literature of the ancient world that it's just that we have to go with pretty much with what we have because there isn't anything else. And every responsible scholar is going to keep that in mind, and is going to nuance that in the text, in the literature that they are producing. And the second consideration is that we still have to take into consideration the prior or intrinsic probabilities of the claims. Like if there is a chronicler that describes three battles and two of the battles, we can actually establish were the case from other sources maybe from archeology and stuff like that. But it's reasonable to believe that he also had accurate information about the third battle from a pragmatic point of view. given that we have no other sources from the ancient world about that particular event. [...] So you wrote about who was elected in what position in that given year, you wrote about important battles, you wrote about things like plagues, crop failure and stuff like that. But you would also dedicate sections to describing divine moments that were observed by people, by the priests, and they were actually reported to the priests like to the state in official capacity because that's very important because you believe that there are the gods. [...] Contemporary historians obviously don't think that those divine omens happened, because that is the difference in intrinsic probability. And it's not their behaving like an anti-supernatural bias or assuming naturalism or being biased against the Roman gods existing or something like that. That's just like doing basic history.

James: If they then write elsewhere about a different event that has no particular connection to the first one, I may not necessarily assume that their account is accurate, especially if in a different place or a different time. The more different it is, basically, the less it seems to fit in the same reference class of things that they could know about, the less I'm going to appeal to that. And so in the case here, what we're talking about is that a certain temple had a certain number of pillars or that a certain pool existed, and some other types of geographic and political references. We're supposed to make some inference about that to details about the claims that the disciples made about their experiences. Those two things to me are completely separate from each other. And just because you're reliable about one doesn't really say anything about reliability on another. So that's the sense in which I just don't agree with that principle at all. It's not just an issue of whether it's the same author, it's about how they would have gotten that information and the plausibility of that information and the bias of the author and other factors like that.

Kamil: it's really apparent that when it comes to this specific type of apologetics, Christian apologists often aim at quantity, not necessarily quality, because I think they realize that they're engaging with an audience either Christian or non-Christian that is in no position to evaluate how significant it is for the author to get that particular historical detail. So they just go with having a lot of them because there is then this implicit cumulative case. But if you actually really go into detail one by one, as you are very well informed about ancient history, you have a robust background knowledge about that, then you will find more often than not that actually, there is nothing particularly striking about an author who wasn't an eyewitness to the events having access to that detail. [...] You will very often see headlines in apologetic websites saying things like 84 things that the Book of Acts got historically correct and the implicit inference that you're supposed to draw from that is, look, if it's the case that the author of Acts got 84 things correct then it's reasonable to believe that either he really was an eyewitness to Paul's life or his missionary journeys, or it's reasonable to believe that he also got the fantastical stuff right. But if you actually look at those 84 things, there are things like there was a temple of Artemis at Ephesus. Well, no surprise! It was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. If this is actually something that I think almost is an argument against the book of Acts being historically reliable. Because if you imagine an author writing a fictional story taking place in a location that he doesn't really know anything about, the one thing that he's going to be talking about is the one thing that everyone knows.

James: There's another issue about base rates. So what is the base rate of correctly ascribing geographic or political or other details like this in fictional texts? We need to establish that if we're going to make claims about how likely it is that a text is accurate, given that it includes some of those details, you need to know what the base rate is, but that's neglected. And this is one of the points that I've continually made here, that they just pull these things out as if they are relevant. But they haven't actually established that they're relevant by looking at comparisons to texts, texts that we generally agree are not accurate. Well, how often do they include these sorts of details?

(this is the same clip as above, but Nathan reads from it here too)

Nathan: "Numerous other discoveries indicate a level of accuracy incompatible with a picture of the development of the gospel as an accretion of legend over the course of two or more generations." I think there's some ambiguity built into the alternative candidate explanations that they sort of set themselves up against here as well, because the gospels as an accretion of legend over the course of two or more generations could mean multiple things. I think that what they're levying and the kind of argument against is the idea that the thing is sort of almost purely fabricated, whereas I think there are quite a lot stronger versions of that where the scaffolding is actually completely historical but then the theological details are given the psychology of like a Second Temple Jew and type of practices to do with history and figuring out what might have happened and all the emotional details that might have been involved in the psychological makeup as well.

James: do they know how much accuracy is incompatible with legendary development? Why wouldn't legends draw upon real places and real things as a way, as a setting for the legends? I'm not saying there were legends but they just make these claims as if they've established some sort of basis, where they haven't.

Kamil: Because this is this is just a summary of what Papias. So if you actually unpack that the things that we can actually independently check about, those accounts are false. Matthew wasn't the first written, Papias says it was written in Hebrew, which it wasn't. [...] I think they [the McGrews] have to basically be committed to those views, even though they are fringe in New Testament scholarship for good reasons. Because alternatively you would have to admit that someone like Papias is wrong about all the things that we can check. But he happens to be right about who wrote it. It's like, you know how in the book of Acts, they want you to say, "Look, the Book of Acts is reliable about all the things that we can check, so it's reasonable to assume that it's reliable." Well, here it's the other way around -- we can establish that Papias is wrong about all the things that we can check. So why believe him about the things that we can't check, which are exactly what's in question, the authorship?

I mention Joseph Francis Burton's excellent series going through Richard Bauchkam's Jesus and the Eyewitnesses. His third video goes through Papias and the evidence we have.

James: Why do we trust these early Christian authors so much -- they don't really justify this. It's not clear what information that they had. Why did they write what they did? Well, I say why did they wrote the gospels, but also why the early Christian authors who were commenting on the gospels wrote their texts? Were they unbiased? Did they follow modern scholarly practices? These are the sort of things that I've been wanting to know in assessing how trustworthy they are. Not just did they write soon afterwards, and some of them is not even that soon afterwards. I just find a total lack of criticism of critical evaluation of the patristic claims and all gospel author claims to be really telling in this section here.

Kamil: This is massively ironic. They say "imaginary strata in an imaginary source document". Do you know what's also an "imaginary strata in an imaginary source document"? The pre-Pauline creeds. We know of the existence of the creeds pretty much from the Pauline Epistles. And it's not certain that those specific passages that are isolated out of the Pauline epistles actually existed and were in circulation about people, you know, before Paul wrote that because it's the best explanation of various features of the text. [...] There is no difference between saying that First Corinthians 15 is pre-Pauline creed and saying that the Q document existed and this is the material from Q. In both cases, we are drawing inferences from from the literary features of the text that we do have about existence of texts that are not actually directly evidenced in the manuscript record.

James: "eyewitnesses who could have contradicted such accounts" How do you know they didn't? This is the question that I always ask when they say so and so would have told against it, would have pulled the body out, would have done whatever -- how do you know they didn't? We have no knowledge either way.